What is Impunity?

Impunity is described as the legal or actual impossibility for the offenders of severe violations of human rights to be accused, caught, tried, or adequately sentenced when found guilty; or for the victims’ damages to be compensated. And of course, impunity emerges from the non-accountability of the offenders of the state as a whole with all its institutions and authorities.

The prevention of impunity is a duty of the state, and states are obliged to investigate, try, and prosecute the offenders who committed grave violations of human rights; to provide victims with effective remedies and to safeguard their right to reparation and right to know; and to act to prevent the repetition of such violations.

In this sense the right to reparations is not limited to compensation only. United Nations Human Rights Council has stated that reparations should include revealing the truth, ‘satisfactory remedies such as restitution, rehabilitation, bringing offenders to book, public apologies (in the sense of accepting the truth and taking the responsibility), building public monuments, and changes and laws and practices to guarantee non-recurrence ’.

The point that States, by signing international treaties and protocols, are obliged and committed to do is to immediately make the necessary legal arrangements (de jure) and to make sure that these laws are put in place in practice (de facto) in order to prevent the repetition of such violations. Not fulfilling these obligations would mean covert support to violations, human rights violations will endure and the offenders of such violations will continue with this behavior through the practice of impunity.

In the struggle against impunity on grave human rights violations, states are responsible towards those whose rights are violated and towards the society to guarantee accountability and to provide and bring to life ‘the Right to Justice’, ‘the Right to Know’, ‘the Right to Reparations’, and ‘the Right to Non-Recurrence’.

Although the phenomenon of impunity comes to the fore more often in the context of grave human rights violations towards political opponents where the state violates its negative obligations such as not killing, not enforcing disappearance, or not torturing, impunity is not limited to this context. The practice of impunity, as a common feature both in the past and at present, prevails with similar extensiveness in all cases where states do not fulfil their positive obligations to protect the right to life. It continues to be a very serious problem as human rights violations towards women, children, or LGBTQ+, hate crimes, and racism are left unpunished.

Article 7 of the Rome Statute: Crimes Against Humanity

When human rights violations are committed against any civil population in a widespread manner and as part of a systematic attack, the situation is defined as a ‘Crime Against Humanity’ in the Rome Statute.

The definition in the Rome Statute is as such:

‘For the purpose of this Statute, “crime against humanity” means any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population:

(1) Murder;

(2) Extermination;

(3) Enslavement;

(4) Deportation or forcible transfer of population;

(5) Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law;

(6) Torture;

(7) Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

(8) Persecution against any identifiable group or collective on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

(9) Enforced disappearance of persons;

(10) Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.

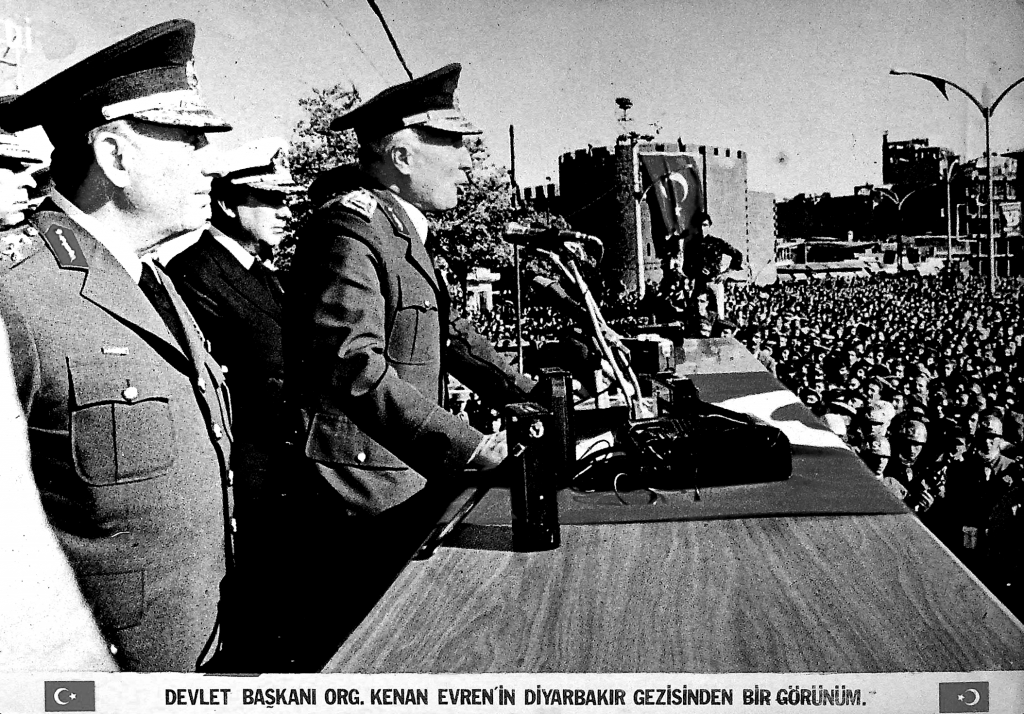

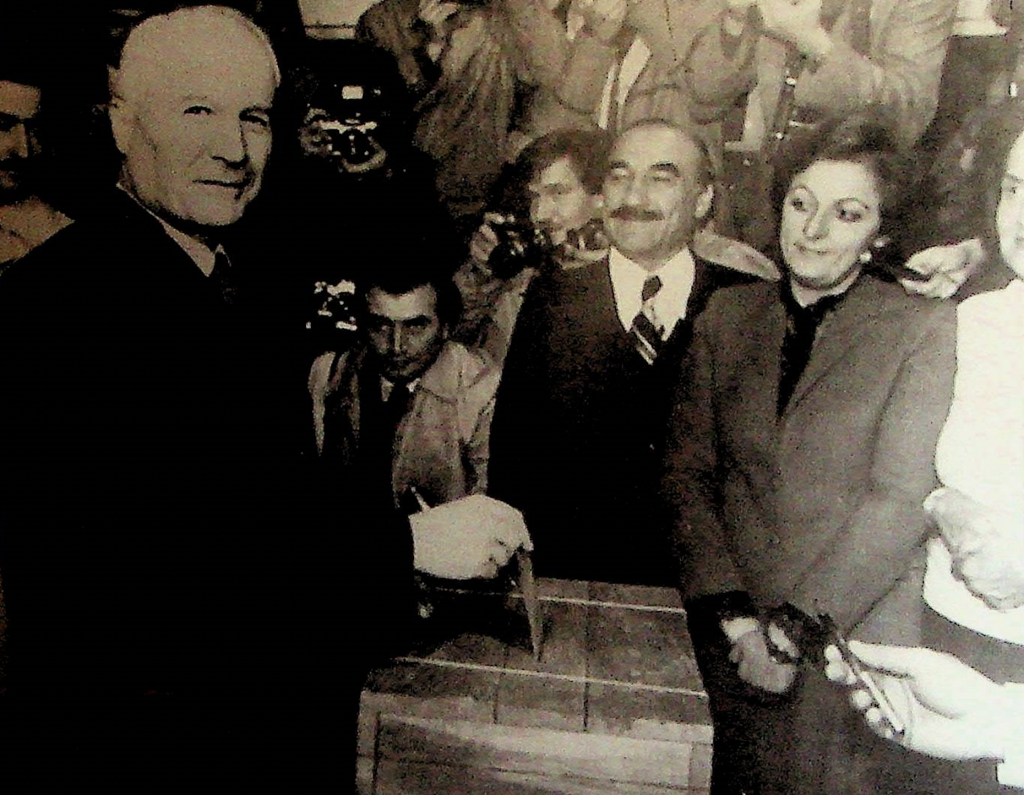

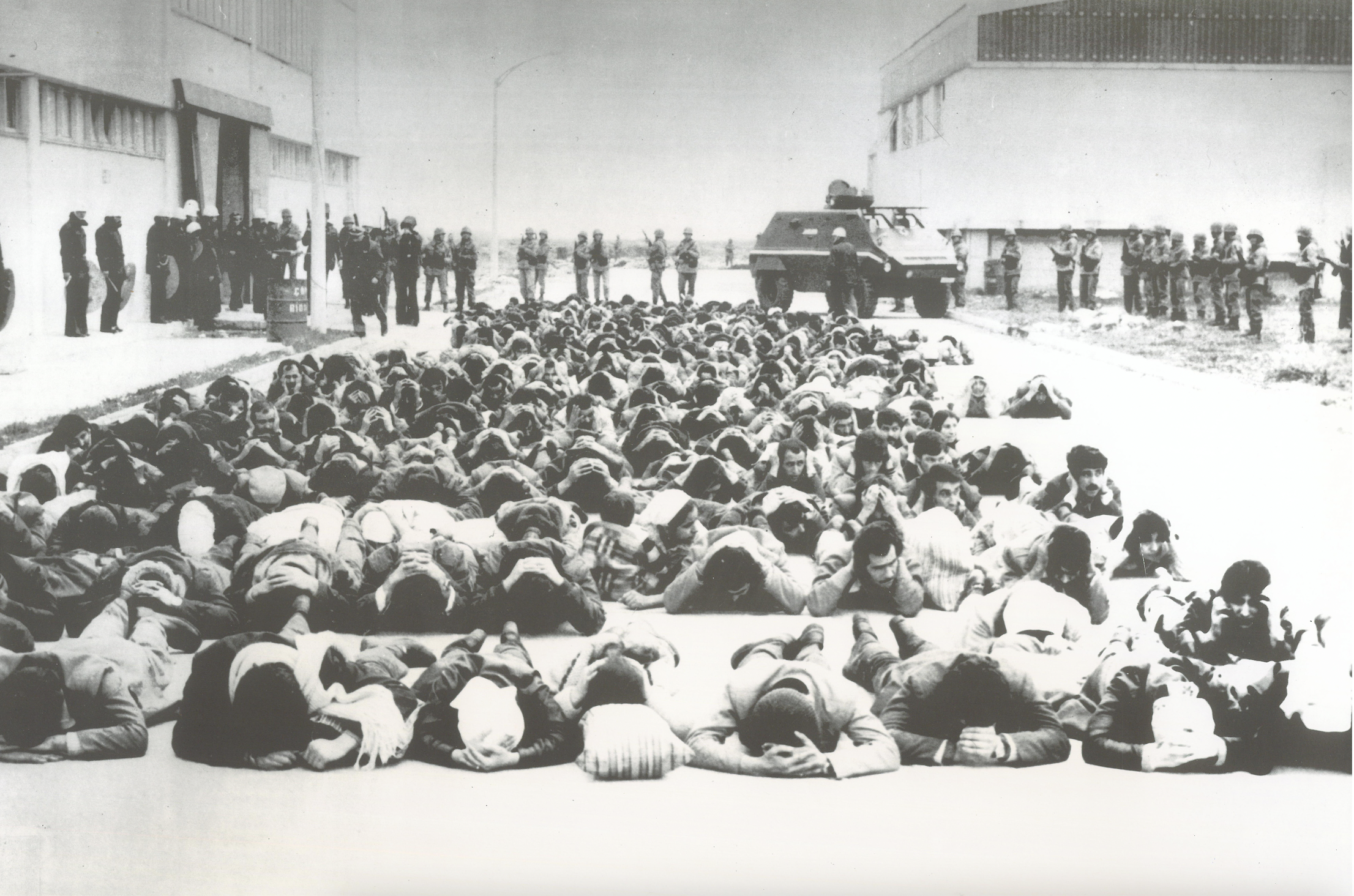

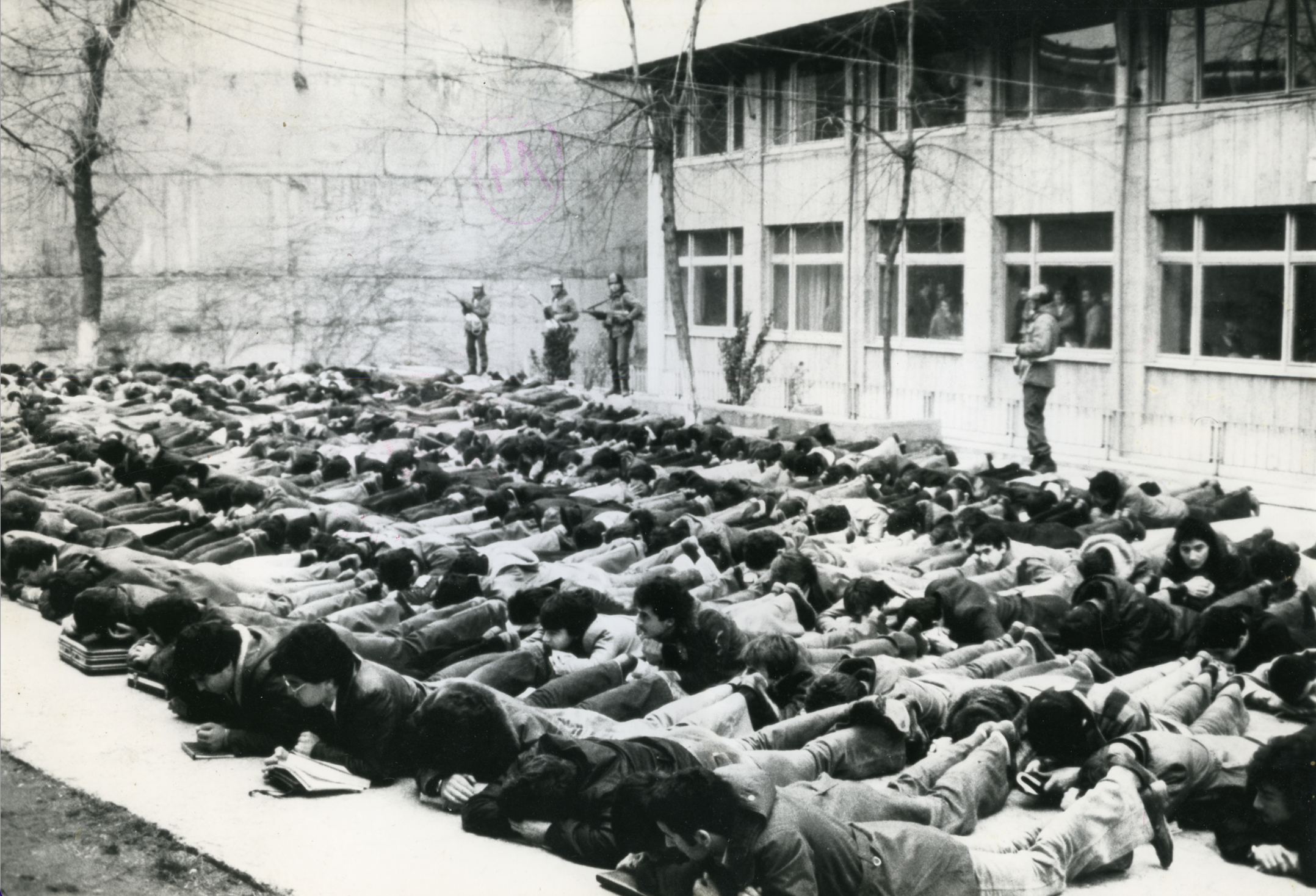

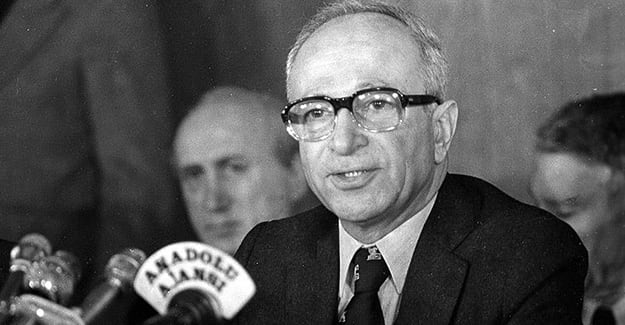

In Turkey, until recently, crimes against humanity had never been discussed or taken into consideration within the Turkish Penal Code or as part of jurisprudence. The concept of crime against humanity was first regulated by the Turkish Penal Law number 5237 which was published and took effect on October 12, 2004, and it was valid for the crimes that would be committed from then on. To date, the systematic and widespread violations of human rights that took place both during the period of September 12 Military Coup and during the 1980s and ’90s have been evaluated as individual crimes of ‘killing’ or singular crimes of ‘torture’, disregarding the obligations brought by international law and this ‘systematic and widespread’ character, and many investigations and prosecutions were thus ended due to expiration of the statute of limitation.

Article 77 of Turkish Penal Code No. 5237 states that;

‘(1) Execution of any one of the following acts systematically under a plan against a sector of a community for political, philosophical, racial or religious reasons, creates the legal consequence of an offenses against humanity.

- a) Deliberate manslaughter, b) Deliberate injury, c) Torturing, infliction of severe suffering, or enslavement, d) depriving someone of personal freedom, e) To subject a person to scientific researches/tests f) Sexual harassment, child molestation, g) Forced pregnancy, h) Forced prostitution.

(2) In case of execution of the act mentioned in paragraph (a) of first subsection, the convict is sentenced to heavy imprisonment; in case of commission of offenses listed in other paragraphs, the convict is sentenced to imprisonment not less than eight years. However, if the offense is caused by voluntary manslaughter or intentional injury of a person, then the provisions relating to physical joinder are applied in consideration of number of victims.

(3) The court may adjudicate imposition of security precautions upon the legal entities due to such offenses. (4) These offenses are not subject to statute of limitation.’

Unlike in Rome Statute, ‘enforced disappearance of persons’ is not included in the definition of the crime in the Turkish Penal Code.

Impunity is described as the legal or actual impossibility for the offenders of severe violations of human rights to be accused, caught, tried, or adequately sentenced when found guilty; or for the victims’ damages to be compensated. And of course, impunity emerges from the non-accountability of the offenders of the state as a whole with all its institutions and authorities.

The prevention of impunity is a duty of the state, and states are obliged to investigate, try, and prosecute the offenders who committed grave violations of human rights; to provide victims with effective remedies and to safeguard their right to reparation and right to know; and to act to prevent the repetition of such violations.

In this sense the right to reparations is not limited to compensation only. United Nations Human Rights Council has stated that reparations should include revealing the truth, ‘satisfactory remedies such as restitution, rehabilitation, bringing offenders to book, public apologies (in the sense of accepting the truth and taking the responsibility), building public monuments, and changes and laws and practices to guarantee non-recurrence ’.

The point that States, by signing international treaties and protocols, are obliged and committed to do is to immediately make the necessary legal arrangements (de jure) and to make sure that these laws are put in place in practice (de facto) in order to prevent the repetition of such violations. Not fulfilling these obligations would mean covert support to violations, human rights violations will endure and the offenders of such violations will continue with this behavior through the practice of impunity.

In the struggle against impunity on grave human rights violations, states are responsible towards those whose rights are violated and towards the society to guarantee accountability and to provide and bring to life ‘the Right to Justice’, ‘the Right to Know’, ‘the Right to Reparations’, and ‘the Right to Non-Recurrence’.

Although the phenomenon of impunity comes to the fore more often in the context of grave human rights violations towards political opponents where the state violates its negative obligations such as not killing, not enforcing disappearance, or not torturing, impunity is not limited to this context. The practice of impunity, as a common feature both in the past and at present, prevails with similar extensiveness in all cases where states do not fulfil their positive obligations to protect the right to life. It continues to be a very serious problem as human rights violations towards women, children, or LGBTQ+, hate crimes, and racism are left unpunished.

Article 7 of the Rome Statute: Crimes Against Humanity

When human rights violations are committed against any civil population in a widespread manner and as part of a systematic attack, the situation is defined as a ‘Crime Against Humanity’ in the Rome Statute.

The definition in the Rome Statute is as such:

‘For the purpose of this Statute, “crime against humanity” means any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population:

(1) Murder;

(2) Extermination;

(3) Enslavement;

(4) Deportation or forcible transfer of population;

(5) Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law;

(6) Torture;

(7) Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

(8) Persecution against any identifiable group or collective on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

(9) Enforced disappearance of persons;

(10) Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.

In Turkey, until recently, crimes against humanity had never been discussed or taken into consideration within the Turkish Penal Code or as part of jurisprudence. The concept of crime against humanity was first regulated by the Turkish Penal Law number 5237 which was published and took effect on October 12, 2004, and it was valid for the crimes that would be committed from then on. To date, the systematic and widespread violations of human rights that took place both during the period of September 12 Military Coup and during the 1980s and ’90s have been evaluated as individual crimes of ‘killing’ or singular crimes of ‘torture’, disregarding the obligations brought by international law and this ‘systematic and widespread’ character, and many investigations and prosecutions were thus ended due to expiration of the statute of limitation.

Article 77 of Turkish Penal Code No. 5237 states that;

‘(1) Execution of any one of the following acts systematically under a plan against a sector of a community for political, philosophical, racial or religious reasons, creates the legal consequence of an offenses against humanity.

- a) Deliberate manslaughter, b) Deliberate injury, c) Torturing, infliction of severe suffering, or enslavement, d) depriving someone of personal freedom, e) To subject a person to scientific researches/tests f) Sexual harassment, child molestation, g) Forced pregnancy, h) Forced prostitution.

(2) In case of execution of the act mentioned in paragraph (a) of first subsection, the convict is sentenced to heavy imprisonment; in case of commission of offenses listed in other paragraphs, the convict is sentenced to imprisonment not less than eight years. However, if the offense is caused by voluntary manslaughter or intentional injury of a person, then the provisions relating to physical joinder are applied in consideration of number of victims.

(3) The court may adjudicate imposition of security precautions upon the legal entities due to such offenses. (4) These offenses are not subject to statute of limitation.’

Unlike in Rome Statute, ‘enforced disappearance of persons’ is not included in the definition of the crime in the Turkish Penal Code.