0001 Museum

Turkey’s first digital museum and human rights archive about the 1980 Coup d’État

0001 Museum

Turkey’s first digital museum and human rights archive about the 1980 Coup d’État

The Memory Museum for Historical Justice holds the records of the crimes against humanity that were committed at the time of the military coup on September 12, 1980 and makes the human rights violations of the era visible.

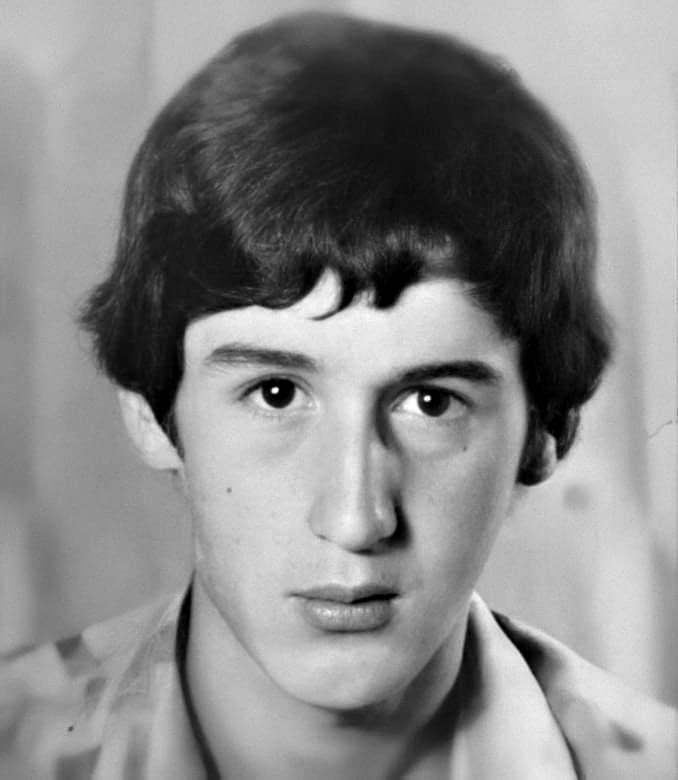

With its collections of Oral History, Court Files and Memory Objects, the Museum provides a digital site of memory for the practices of dealing with the past and the ongoing struggle for justice for the last 42 years. As an open, democratic and collective platform, it commonizes history bottom-up.

As a human rights archive, the documents in the collections of the Memory Museum will shed light on the struggle of those who were targeted during this period and more specifically on the social and legal processes that took place between 1970 and 1990.

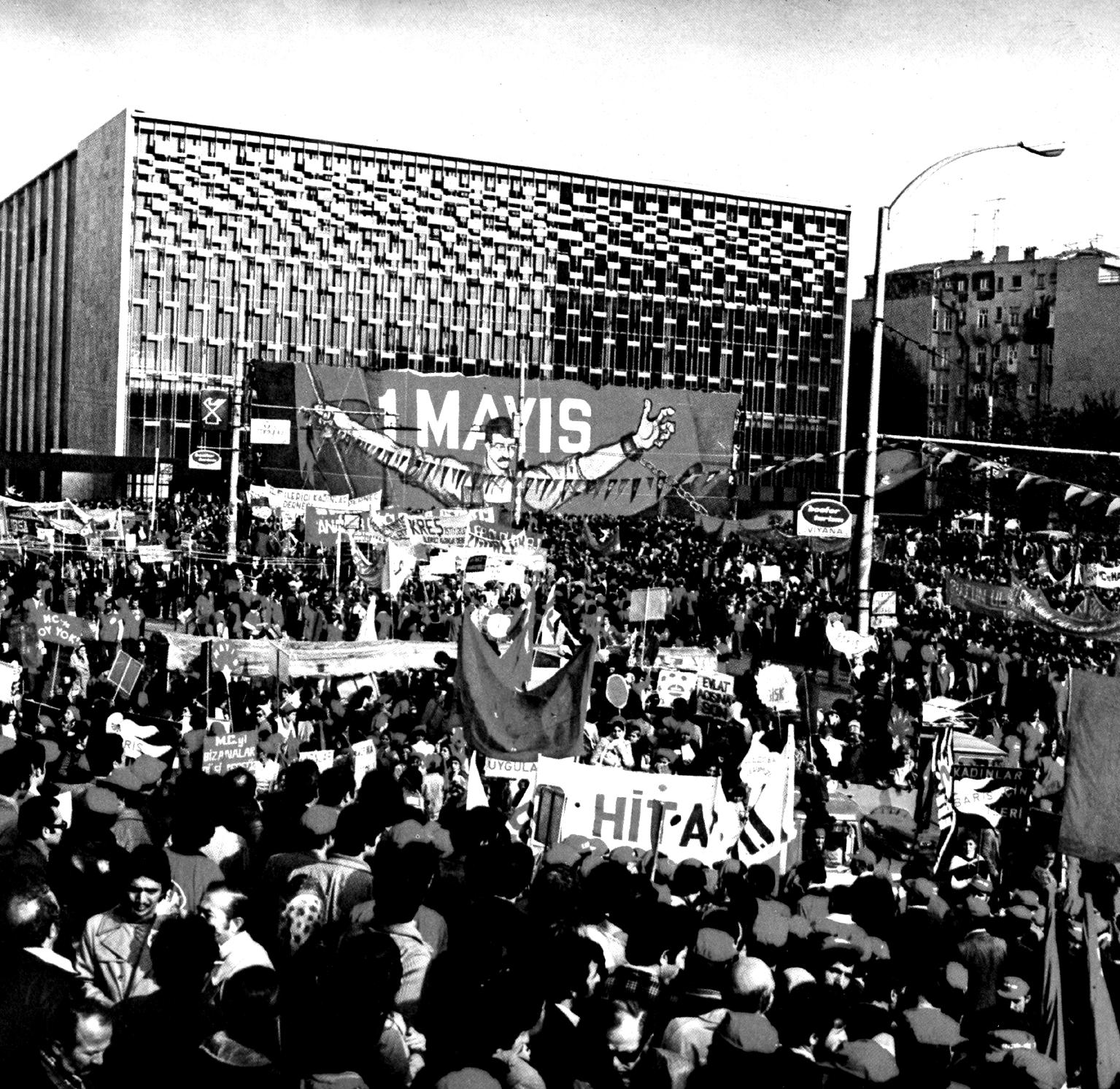

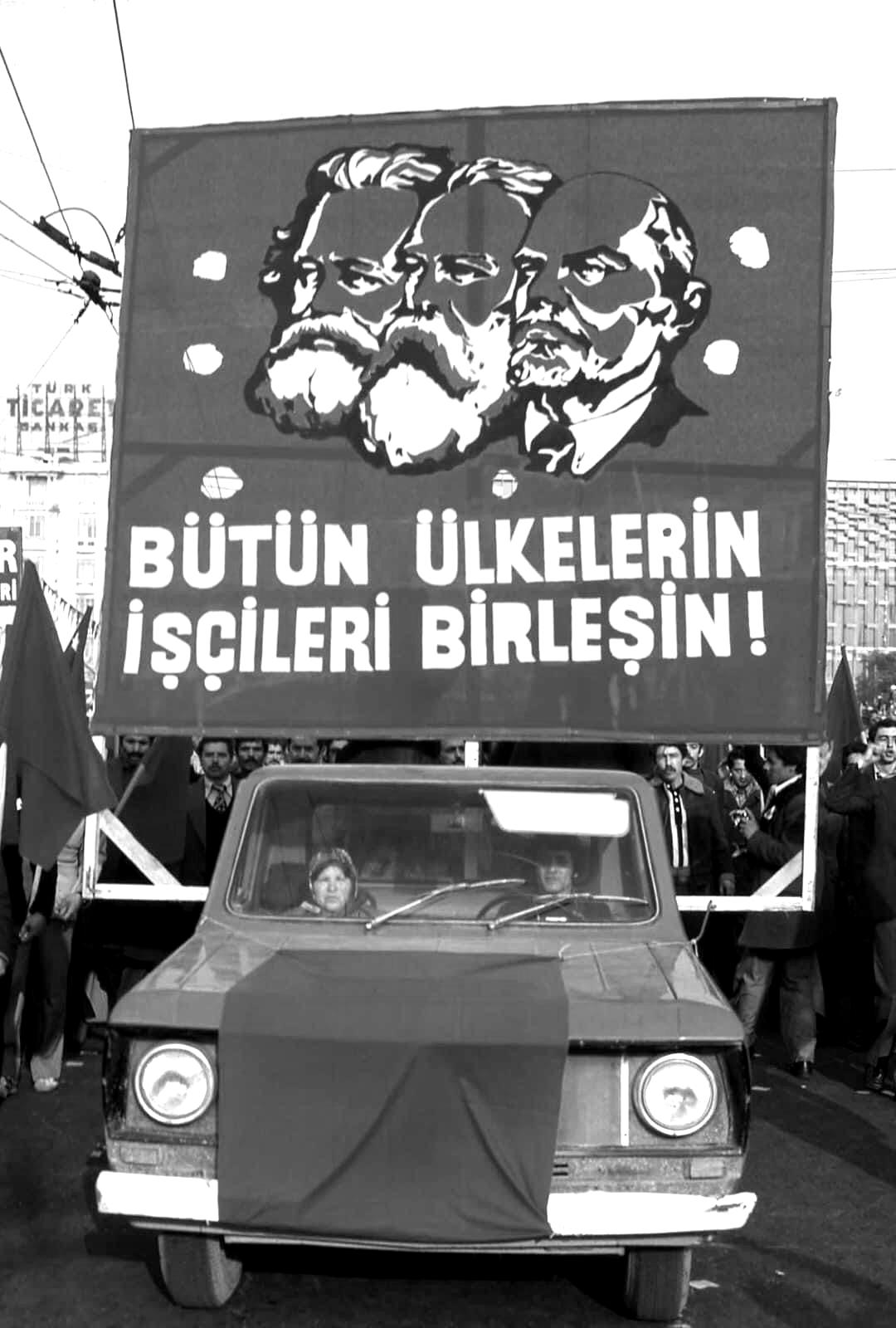

In addition to numerous testimonies on issues that range from the rise of the revolutionary struggle and the student movement to union organizations, from women’s political struggle to anti-fascist resistance, the Museum presents information about the collective memory of the Coup, the military regime and its legal system, violations of human rights, the struggle for justice, international solidarity, impunity, and the practices of reconciliation and accountability.

Memory Museum for Historical Justice came to life as a research of the Collective Memory Working Group of the Research Institute on Turkey. The institutions, human rights organizations, attorneys, rights defenders, witnesses, academics and writers came together for a common cause: to gather data on the 1980 Coup d’État, to understand the everlasting effects of the Coup in the light of historical documents and information, and to actively take part in the struggle for democracy.

The Memory Museum for Historical Justice holds the records of the crimes against humanity that were committed at the time of the military coup on September 12, 1980 and makes the human rights violations of the era visible.

With its collections of Oral History, Court Files and Memory Objects, the Museum provides a digital site of memory for the practices of dealing with the past and the ongoing struggle for justice for the last 42 years. As an open, democratic and collective platform, it commonizes history bottom-up.

As a human rights archive, the documents in the collections of the Memory Museum will shed light on the struggle of those who were targeted during this period and more specifically on the social and legal processes that took place between 1970 and 1990.

In addition to numerous testimonies on issues that range from the rise of the revolutionary struggle and the student movement to union organizations, from women’s political struggle to anti-fascist resistance, the Museum presents information about the collective memory of the Coup, the military regime and its legal system, violations of human rights, the struggle for justice, international solidarity, impunity, and the practices of reconciliation and accountability.

Memory Museum for Historical Justice came to life as a research of the Collective Memory Working Group of the Research Institute on Turkey. The institutions, human rights organizations, attorneys, rights defenders, witnesses, academics and writers came together for a common cause: to gather data on the 1980 Coup d’État, to understand the everlasting effects of the Coup in the light of historical documents and information, and to actively take part in the struggle for democracy.

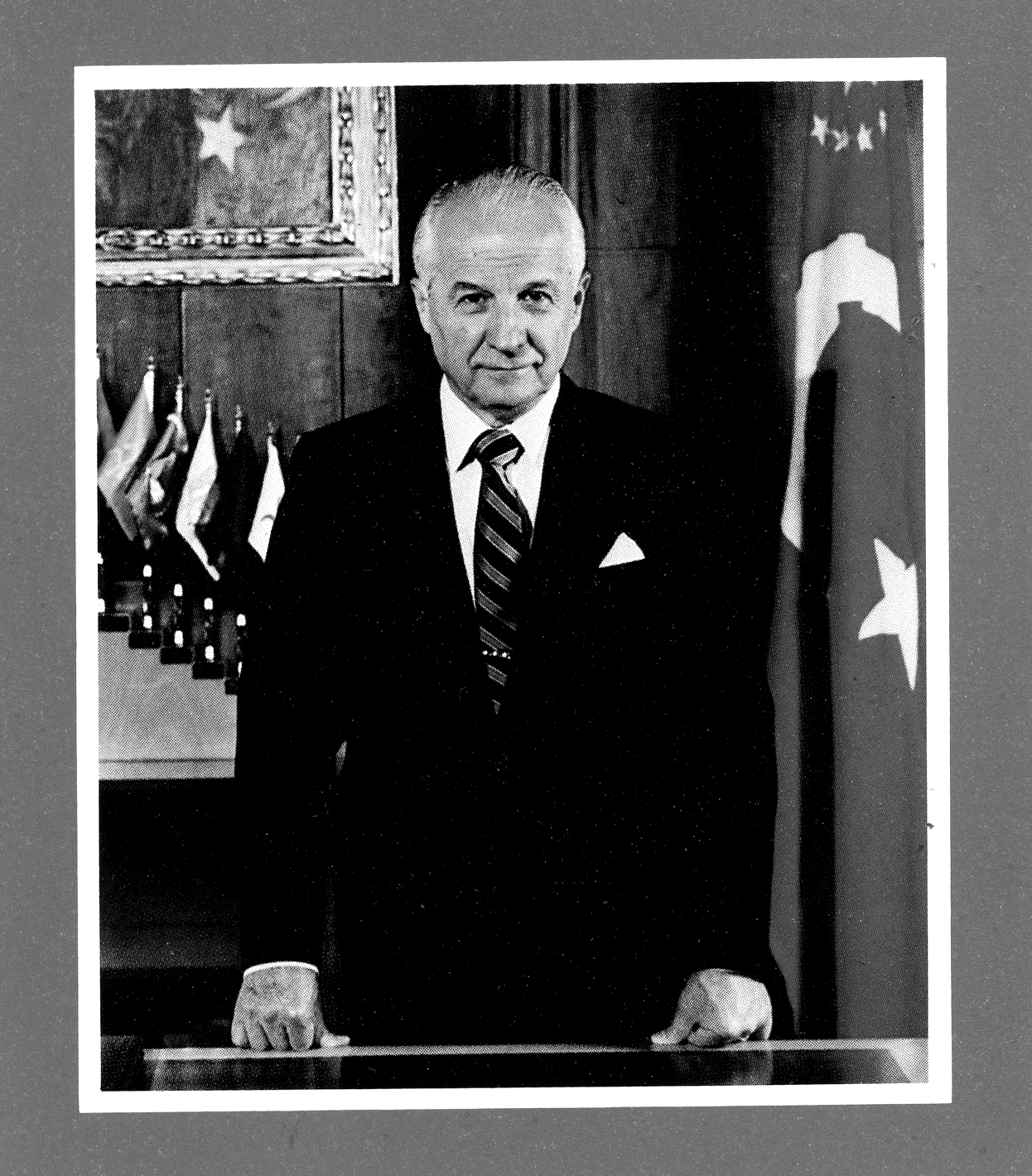

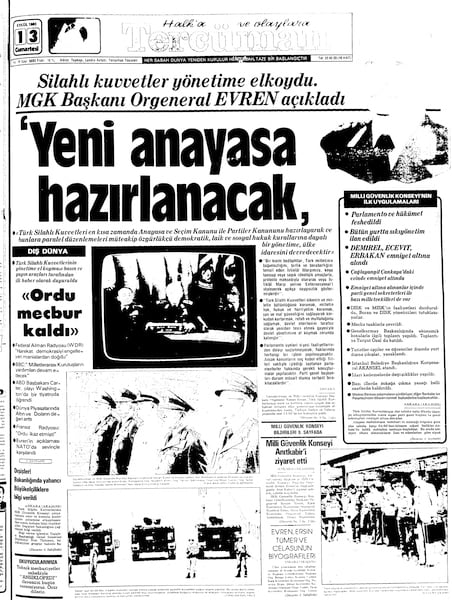

On September 12, 1980, the Turkish Armed Forces carried out the third successful military coup in the history of the Republic of Turkey. The ‘Flag Operation’ was carried out in a chain of command under the leadership of Chief of Staff Kenan Evren, and the army seized control of the country. At 4.00 a.m., the Proclamation No. 1 of the Coup was announced by Kenan Evren as the Chief of Staff and the President of the National Security Council (NSC) via the Turkish Radio-Television Channel and was also delivered through PTT (Post Telegraph and Telephone).

On September 12, 1980, the Turkish Armed Forces carried out the third successful military coup in the history of the Republic of Turkey. The ‘Flag Operation’ was carried out in a chain of command under the leadership of Chief of Staff Kenan Evren, and the army seized control of the country. At 4.00 a.m., the Proclamation No. 1 of the Coup was announced by Kenan Evren as the Chief of Staff and the President of the National Security Council (NSC) via the Turkish Radio-Television Channel and was also delivered through PTT (Post Telegraph and Telephone).

It was declared that ‘The aim of the operation is to protect the integrity of the country, to ensure national unity and solidarity, to prevent a possible civil war and a fight among brothers, to re-establish the authority and presence of the state, and to eliminate the reasons that prevent the democratic order from functioning…’.

From this moment on, through its proclamations, decrees and laws, the National Security Council took over the legislative and constitutional authority and imposed regulations in various fields.

It was declared that ‘The aim of the operation is to protect the integrity of the country, to ensure national unity and solidarity, to prevent a possible civil war and a fight among brothers, to re-establish the authority and presence of the state, and to eliminate the reasons that prevent the democratic order from functioning…’.

From this moment on, through its proclamations, decrees and laws, the National Security Council took over the legislative and constitutional authority and imposed regulations in various fields.

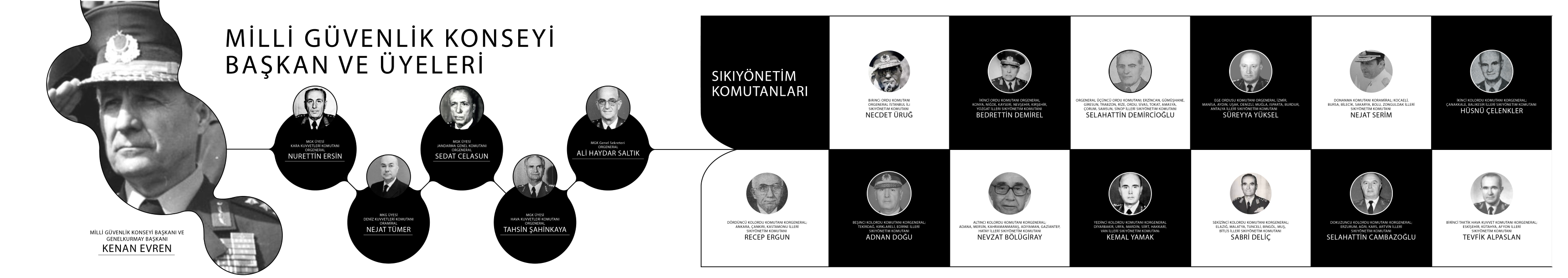

As declared in the Proclamation No. 4 of the NSC, National Security Council consisted of Chief of Staff Kenan Evren (President), Commander of Naval Forces Full Admiral Nejat Tümer, Commander of Land Forces Full General Nurettin Ersin, Commander of Air Forces, Full General Tahsin Şahinkaya, and Commander of Gendarmerie Forces Full General Sedat Celasun, and Full General Haydar Saltık as the Secretary General.

With the Proclamation No. 1 of the NSC, the Parliament and the Government were dissolved. The immunities of the members of the parliament were revoked. Martial law, which had already been in place in 22 provinces, was imposed on the whole country. Starting from 5 a.m. on the same day, indefinite and nationwide curfew was ordered.

With the Proclamation No. 2 of the NSC, Turkey was divided into thirteen regions of martial law, and for each region a full general was appointed as the martial law regional commander. The regional martial law commanders were endowed with ‘the authority to make all regulations and to take all measures they deem necessary’, which meant an unlimited power per se. With the Decisions No. 6 and 7 of the NSC, martial law military courts were established and NSC assumed the full authority to appoint judges and prosecutors to these courts.

As declared in the Proclamation No. 4 of the NSC, National Security Council consisted of Chief of Staff Kenan Evren (President), Commander of Naval Forces Full Admiral Nejat Tümer, Commander of Land Forces Full General Nurettin Ersin, Commander of Air Forces, Full General Tahsin Şahinkaya, and Commander of Gendarmerie Forces Full General Sedat Celasun, and Full General Haydar Saltık as the Secretary General.

With the Proclamation No. 1 of the NSC, the Parliament and the Government were dissolved. The immunities of the members of the parliament were revoked. Martial law, which had already been in place in 22 provinces, was imposed on the whole country. Starting from 5 a.m. on the same day, indefinite and nationwide curfew was ordered.

With the Proclamation No. 2 of the NSC, Turkey was divided into thirteen regions of martial law, and for each region a full general was appointed as the martial law regional commander. The regional martial law commanders were endowed with ‘the authority to make all regulations and to take all measures they deem necessary’, which meant an unlimited power per se. With the Decisions No. 6 and 7 of the NSC, martial law military courts were established and NSC assumed the full authority to appoint judges and prosecutors to these courts.

With the law numbered 2337, dated November 7, 1980, an amendment was made on Act 15 of the Law No. 1402 on Martial Law Governance, increasing the period of custody to ninety days.

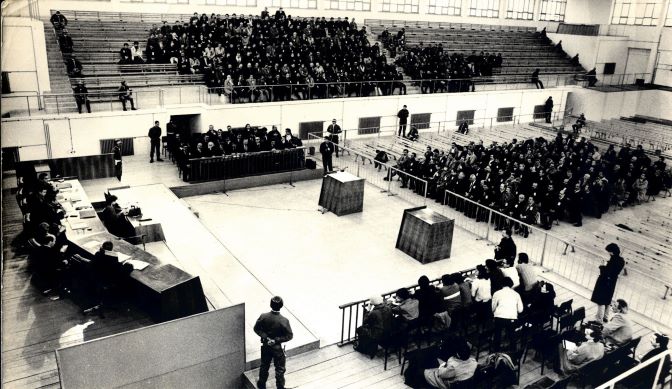

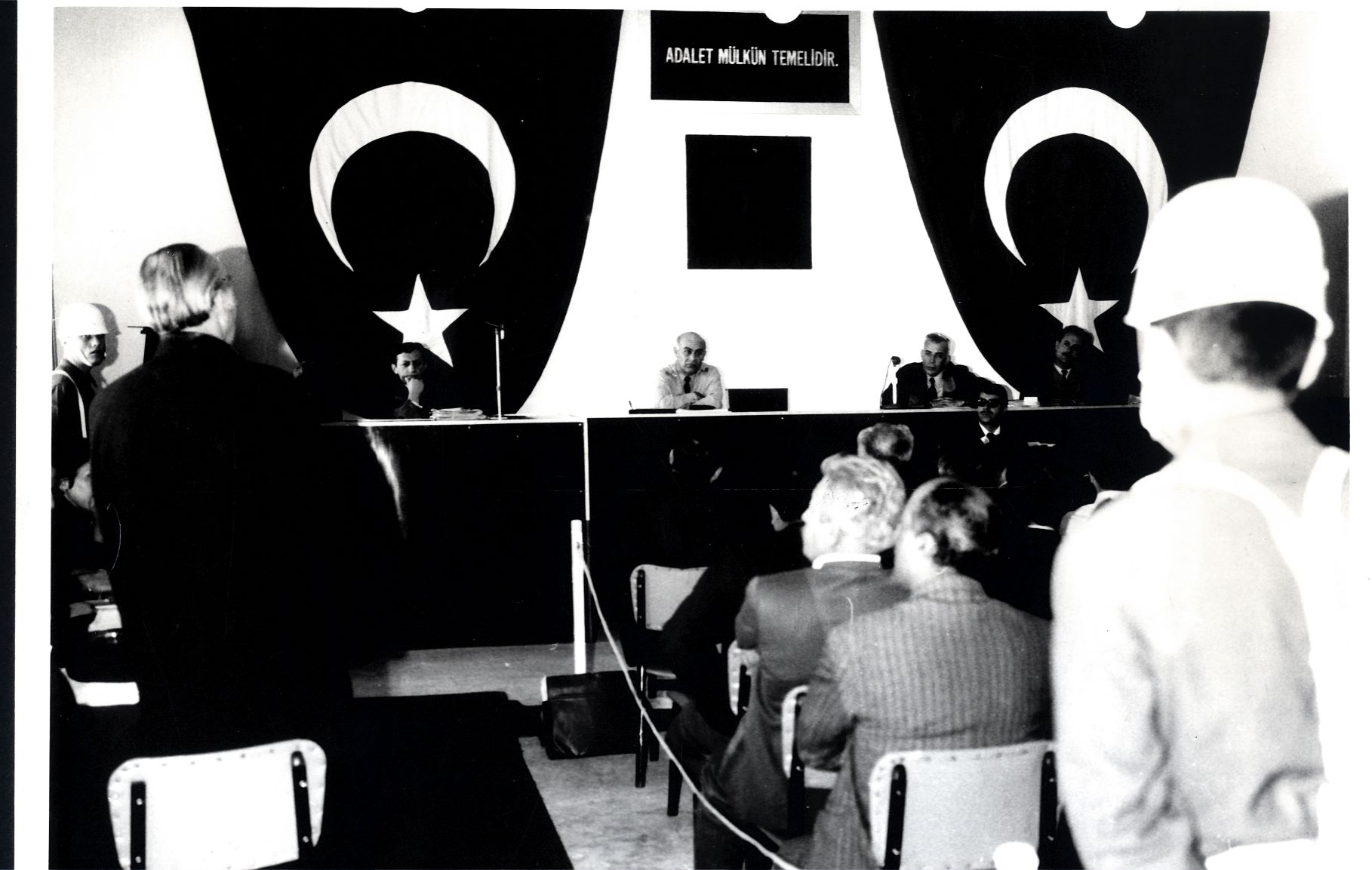

The judicial organs installed by the NSC became the most substantial organs of the 1980 Coup period. The martial law courts and the Supreme Military Court were allegiant to political orders, military prompting and pressure, and acted in line with the main aims of the 1980 Coup, specifically through the new legal interpretations they brought to Acts numbered 141, 142, 146, 168, 169 and 125 of the Turkish Penal Code No. 765.

With the law numbered 2337, dated November 7, 1980, an amendment was made on Act 15 of the Law No. 1402 on Martial Law Governance, increasing the period of custody to ninety days.

The judicial organs installed by the NSC became the most substantial organs of the 1980 Coup period. The martial law courts and the Supreme Military Court were allegiant to political orders, military prompting and pressure, and acted in line with the main aims of the 1980 Coup, specifically through the new legal interpretations they brought to Acts numbered 141, 142, 146, 168, 169 and 125 of the Turkish Penal Code No. 765.

With the Proclamation No. 6 of the NSC, the staff of the Turkish Armed Forces would continue their duties under the chain of command. With the Proclamation No. 9 of the NSC, the General Directorate of Security (Police Department) at its entirety was relocated under the command and institution of the General Commandership of Gendarmerie. Lieutenant General Hayrettin Tulunay was appointed as the General Director of the Police Department.

With the Proclamation No. 6 of the NSC, the staff of the Turkish Armed Forces would continue their duties under the chain of command. With the Proclamation No. 9 of the NSC, the General Directorate of Security (Police Department) at its entirety was relocated under the command and institution of the General Commandership of Gendarmerie. Lieutenant General Hayrettin Tulunay was appointed as the General Director of the Police Department.

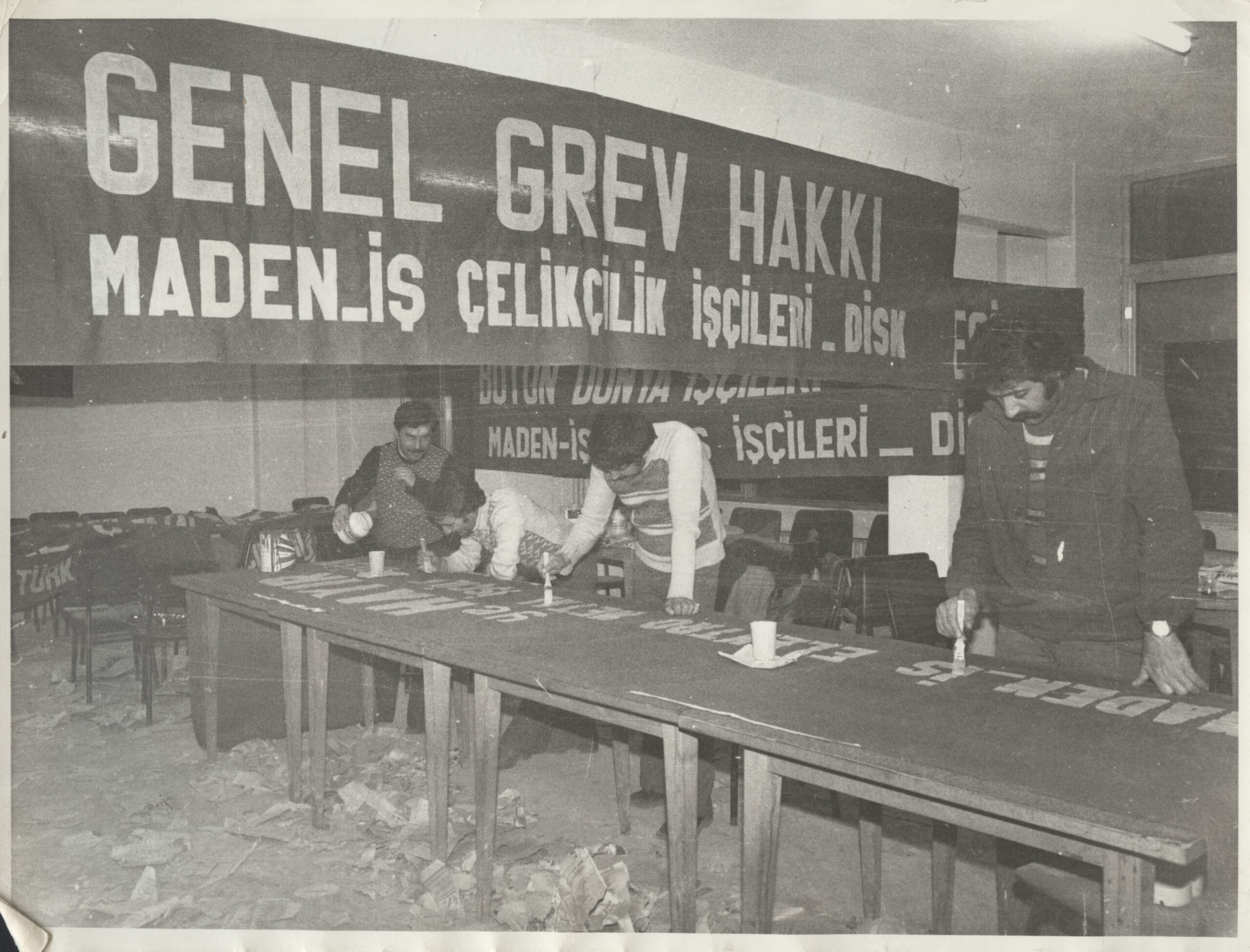

With the Proclamation No. 7 of the NSC, political party activities were banned. Party and union buildings and facilities were confiscated by the martial law and garrison commandership. The activities of DİSK (Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions of Turkey) and MİSK (Confederation of Nationalist Trade Unions of Turkey), and the associated unions were halted. All activities of all associations except Turkish Aviation Association, the Society for the Protection of Children, and the Turkish Red Crescent were stopped. On June 2, 1981, the National Security Council, with its Decision Numbered 52, banned the members and directors of the political parties that had seats in the parliament as of September 11, 1980 from making any oral or written statements declaring their own viewpoints on Turkey’s past and future political and legal structure, write articles on these issues, or hold meetings to that end. The Law on the Abolition of Political Parties, dated October 16, 1981, and numbered 1533, abolished all of the political parties that were active as of September 11, 1980, and their estates and assets were seized.

With Proclamation No. 15 of the National Security Council, all strikes and lockouts were canceled until a further decision. All workplaces were reinforced to commence industrial production on September 15, 1980, in the morning. With the Proclamation No. 8 of the NSC, dated September 15, 1980, the financial accounts of DİSK, MİSK and Hak-İş ([Islamist] Confederation of Turkish Real Trade Unions) and the unions that constitute them were frozen.

With the law that amended the Law No. 1402 on Martial Law Governance, that was published on the Official Gazette on September 21, 1980, martial law commanders were endowed with the authority to terminate indefinitely or subject to permission the union activities such as strikes, lockouts or declarations of intention.

On September 25, 1980, with the Republic of Turkey National Security Council Legislative Duties Ordinance, the National Security Council took over the authority to legislate. On October 27, 1980, with the Law on Constitutional Order, which meant a temporary constitution, NSC also took over the authority to make amendments on the Constitution. Until the end of 1981 only, the NSC passed a total of 268 laws, 51 of which were new. The laws were specifically about security, penal code and criminal procedure, the execution of death sentences, and the needs of the Turkish Armed Forces. During the military regime, a total of 669 laws were passed. With the Law on the Constituent Assembly, dated June 29, 1981, the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the NSC and its Advisory Assembly, was given the duty to draw the constitution and all necessary laws. All members of the Advisory Assembly would be selected by the NSC either directly (40 members) or indirectly (from among the candidates named by provincial governors to represent each province). The Advisory Assembly held its first meeting on October 23, 1981.

The Proclamation No. 3 of the NSC regulated how the vital needs of people would be fulfilled during the curfew and the permissions should be obtained from the garrison commanderships.

The Proclamation No. 8 of the NSC halted all retirement, resignation, release and reassignment procedures of all civil servants, contract employees and paid staff working in government offices, municipalities, public economic enterprises and autonomous state institutions.

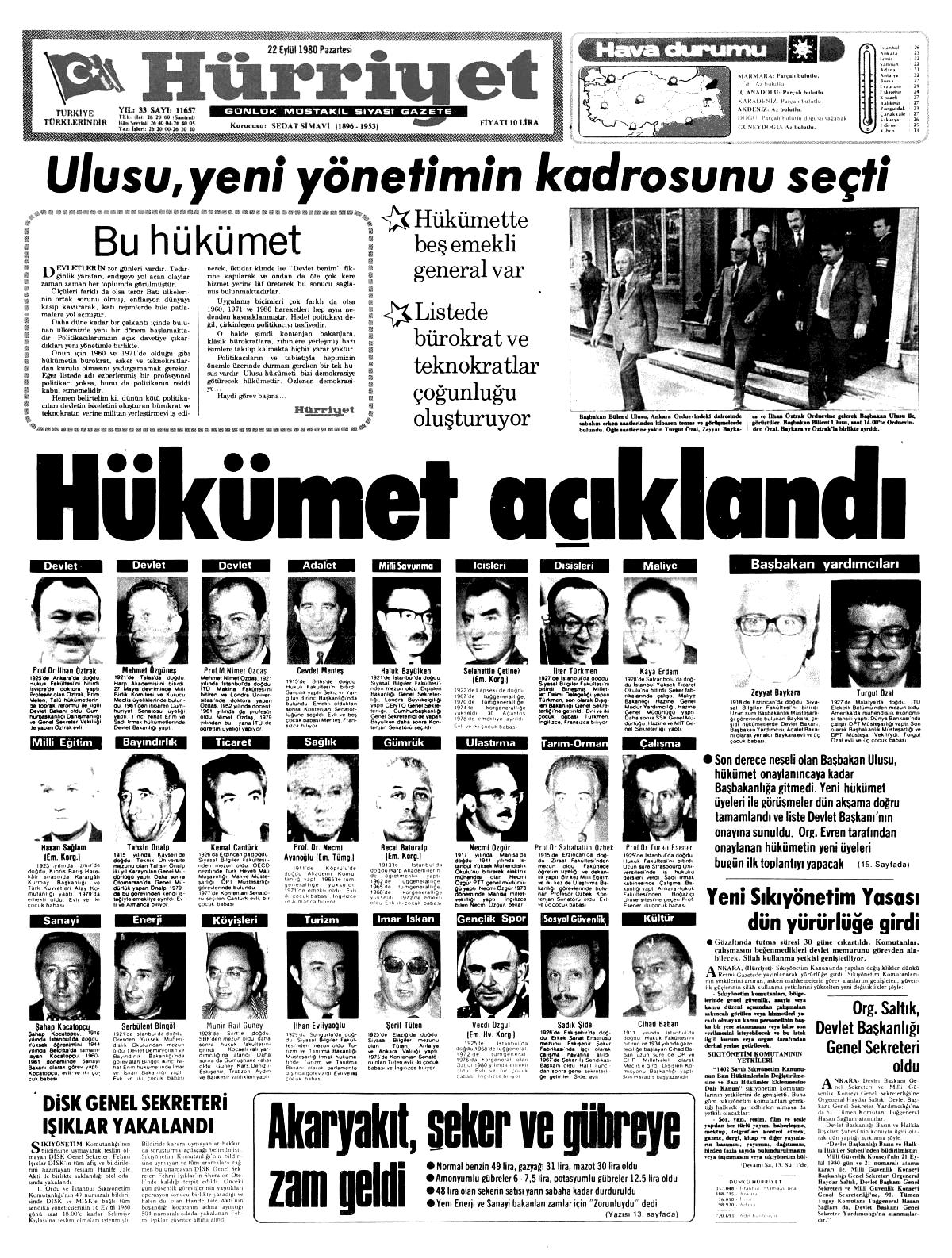

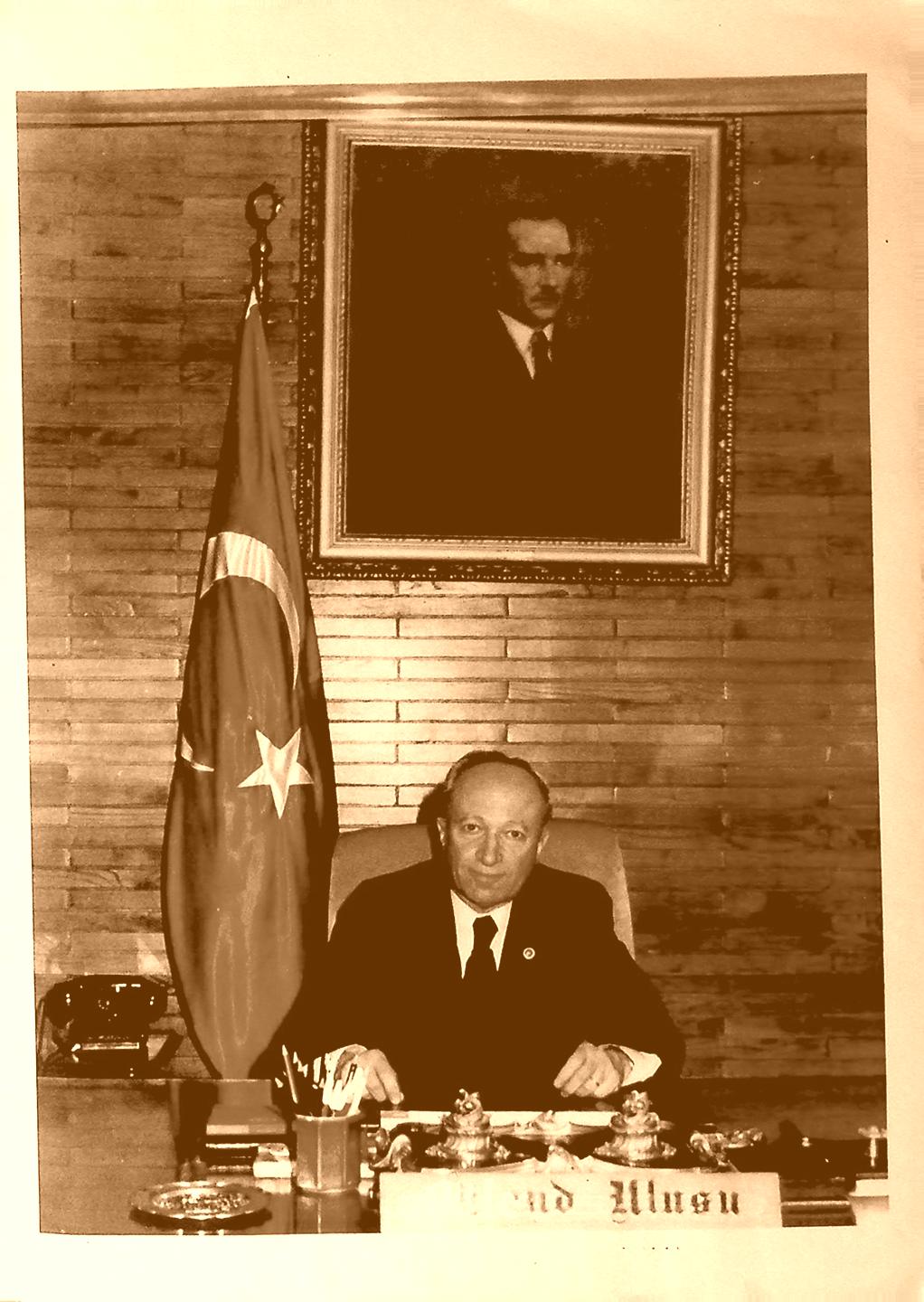

On a writ dated September 20, 1980, Kenan Evren, with the title of the President of the State, Chief of Staff, and the President of the NSC; appointed the retired Full Admiral Bülend Ulusu as Prime Minister and asked him to name the members of the Cabinet of his own choice.

With the Proclamation No. 7 of the NSC, political party activities were banned. Party and union buildings and facilities were confiscated by the martial law and garrison commandership. The activities of DİSK (Confederation of Revolutionary Trade Unions of Turkey) and MİSK (Confederation of Nationalist Trade Unions of Turkey), and the associated unions were halted. All activities of all associations except Turkish Aviation Association, the Society for the Protection of Children, and the Turkish Red Crescent were stopped. On June 2, 1981, the National Security Council, with its Decision Numbered 52, banned the members and directors of the political parties that had seats in the parliament as of September 11, 1980 from making any oral or written statements declaring their own viewpoints on Turkey’s past and future political and legal structure, write articles on these issues, or hold meetings to that end. The Law on the Abolition of Political Parties, dated October 16, 1981, and numbered 1533, abolished all of the political parties that were active as of September 11, 1980, and their estates and assets were seized.

With Proclamation No. 15 of the National Security Council, all strikes and lockouts were canceled until a further decision. All workplaces were reinforced to commence industrial production on September 15, 1980, in the morning. With the Proclamation No. 8 of the NSC, dated September 15, 1980, the financial accounts of DİSK, MİSK and Hak-İş ([Islamist] Confederation of Turkish Real Trade Unions) and the unions that constitute them were frozen.

With the law that amended the Law No. 1402 on Martial Law Governance, that was published on the Official Gazette on September 21, 1980, martial law commanders were endowed with the authority to terminate indefinitely or subject to permission the union activities such as strikes, lockouts or declarations of intention.

On September 25, 1980, with the Republic of Turkey National Security Council Legislative Duties Ordinance, the National Security Council took over the authority to legislate. On October 27, 1980, with the Law on Constitutional Order, which meant a temporary constitution, NSC also took over the authority to make amendments on the Constitution. Until the end of 1981 only, the NSC passed a total of 268 laws, 51 of which were new. The laws were specifically about security, penal code and criminal procedure, the execution of death sentences, and the needs of the Turkish Armed Forces. During the military regime, a total of 669 laws were passed. With the Law on the Constituent Assembly, dated June 29, 1981, the Constituent Assembly, which was formed by the NSC and its Advisory Assembly, was given the duty to draw the constitution and all necessary laws. All members of the Advisory Assembly would be selected by the NSC either directly (40 members) or indirectly (from among the candidates named by provincial governors to represent each province). The Advisory Assembly held its first meeting on October 23, 1981.

The Proclamation No. 3 of the NSC regulated how the vital needs of people would be fulfilled during the curfew and the permissions should be obtained from the garrison commanderships.

The Proclamation No. 8 of the NSC halted all retirement, resignation, release and reassignment procedures of all civil servants, contract employees and paid staff working in government offices, municipalities, public economic enterprises and autonomous state institutions.

On a writ dated September 20, 1980, Kenan Evren, with the title of the President of the State, Chief of Staff, and the President of the NSC; appointed the retired Full Admiral Bülend Ulusu as Prime Minister and asked him to name the members of the Cabinet of his own choice.

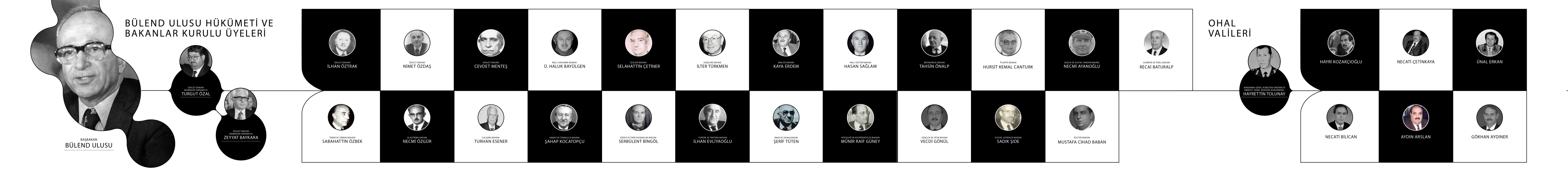

The Bülend Ulusu Government, which was formed only nine days after the 1980 Coup d’État, presented its government program to the National Security Council on September 27, 1980. On September 30, 1980 this government obtained its vote of confidence from the NSC instead of the parliament, which had been abolished.

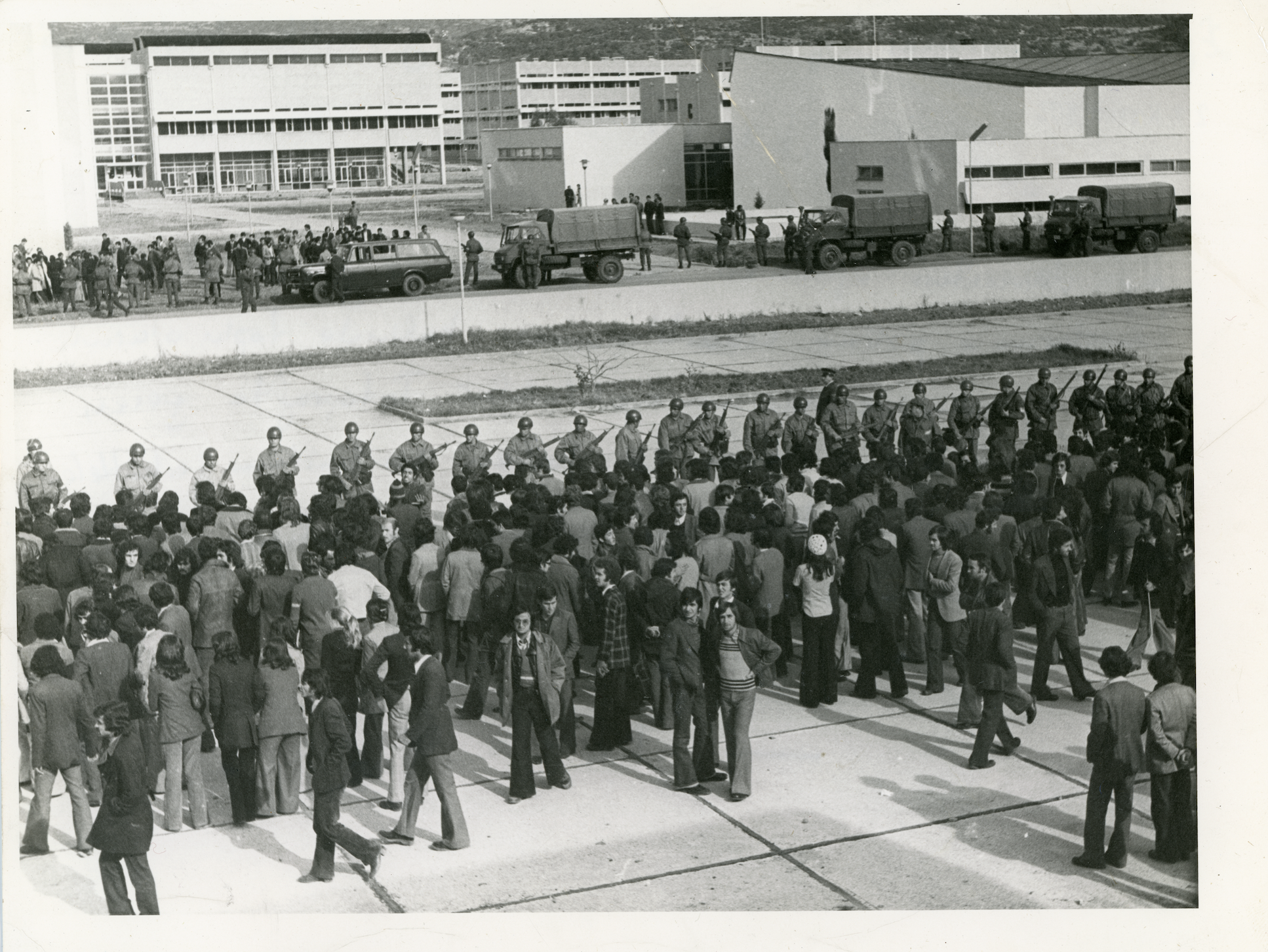

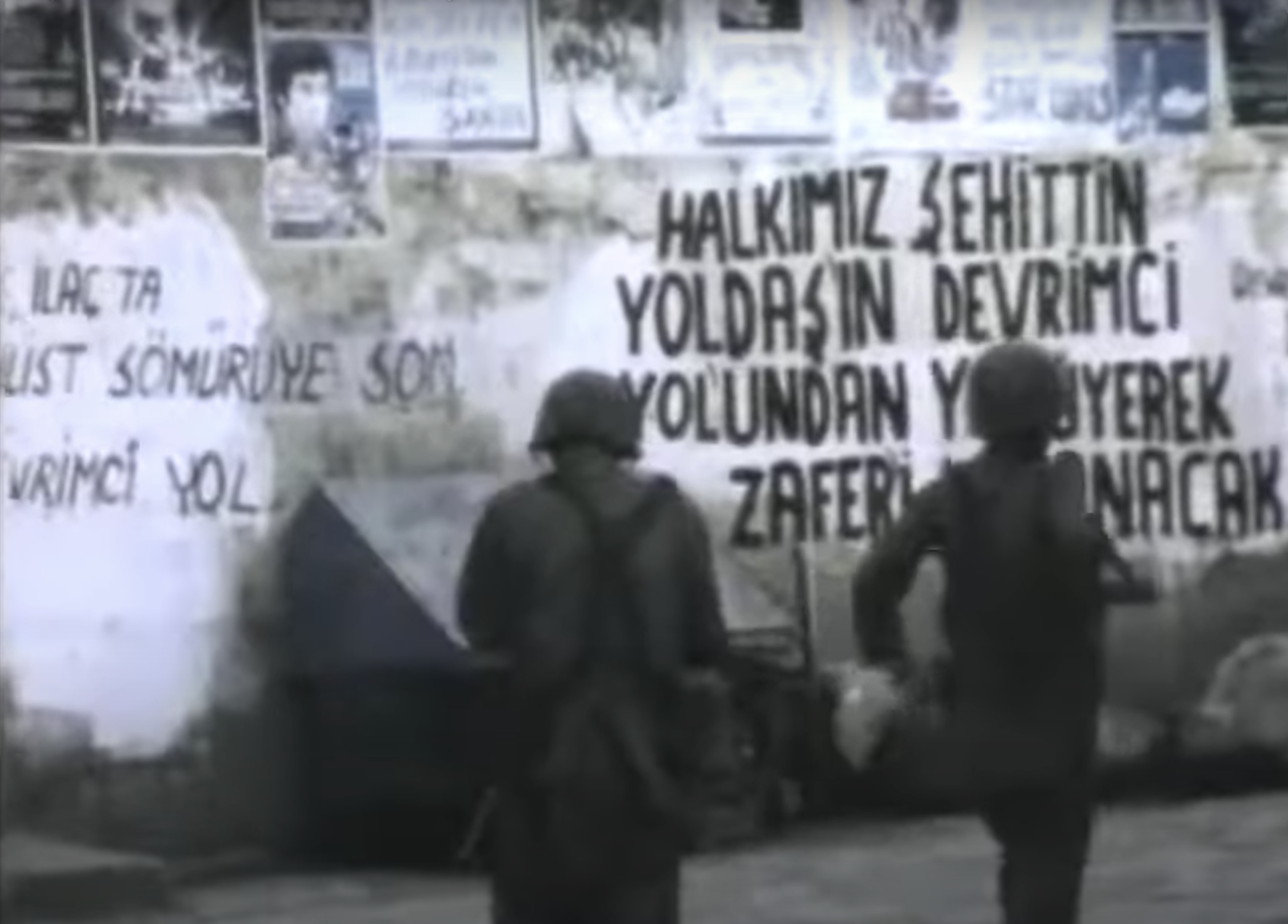

The main targets of the September 12, 1980 Coup d’État and the regime were the social, syndical and political organizations of the working class. To this end, the short-term strategy of the state was to employ policies of violence and oppression, while the long-term strategy was to restructure the institutional architecture of the state in a way that would disable the political empowerment of this section of the society.

The Bülend Ulusu Government, which was formed only nine days after the 1980 Coup d’État, presented its government program to the National Security Council on September 27, 1980. On September 30, 1980 this government obtained its vote of confidence from the NSC instead of the parliament, which had been abolished.

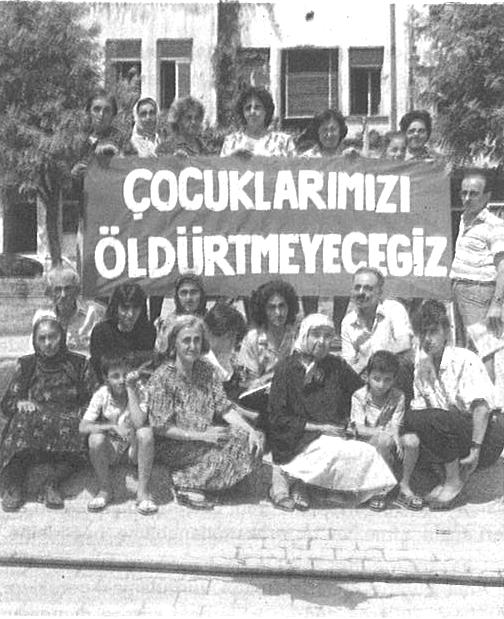

The main targets of the September 12, 1980 Coup d’État and the regime were the social, syndical and political organizations of the working class. To this end, the short-term strategy of the state was to employ policies of violence and oppression, while the long-term strategy was to restructure the institutional architecture of the state in a way that would disable the political empowerment of this section of the society.

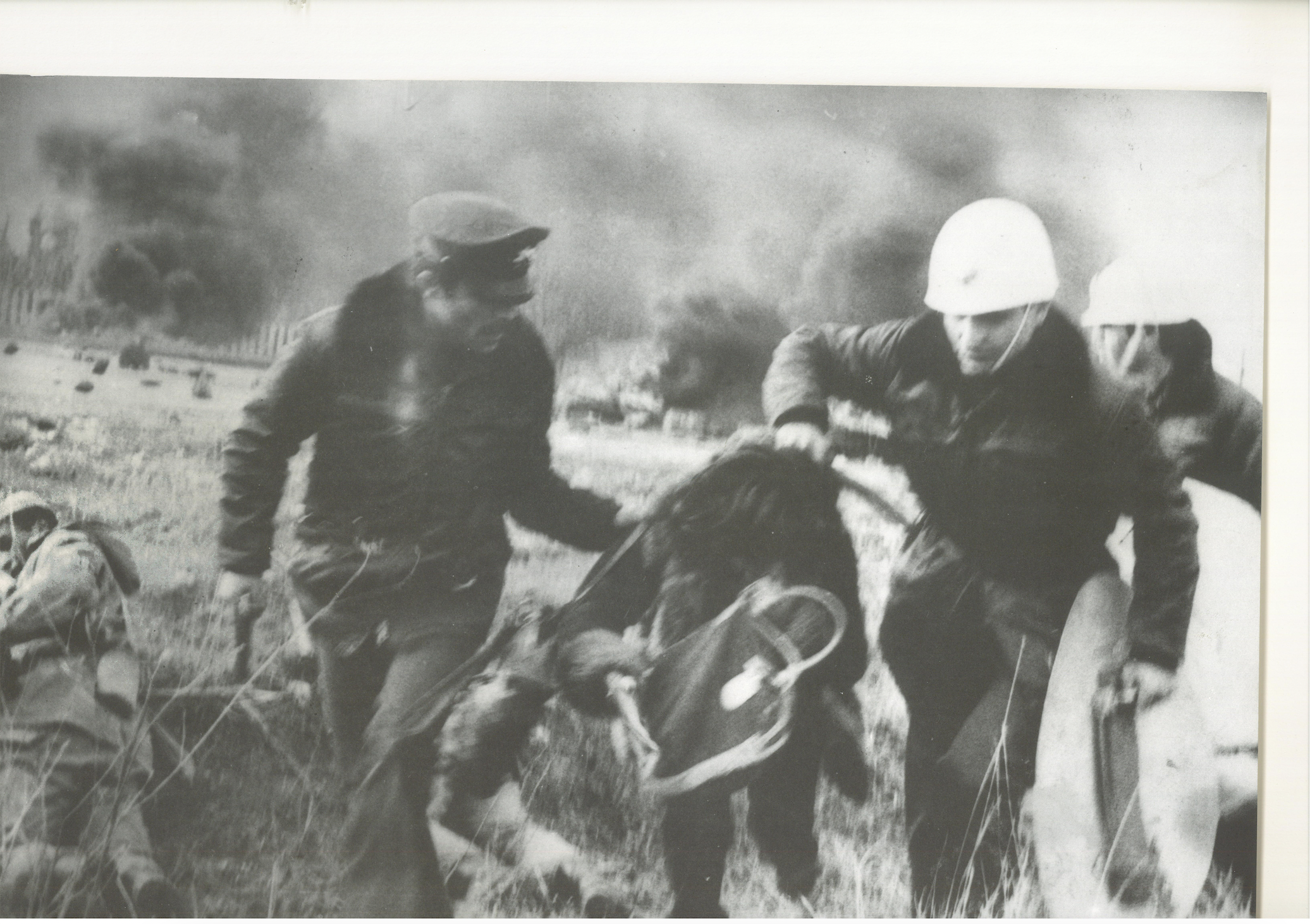

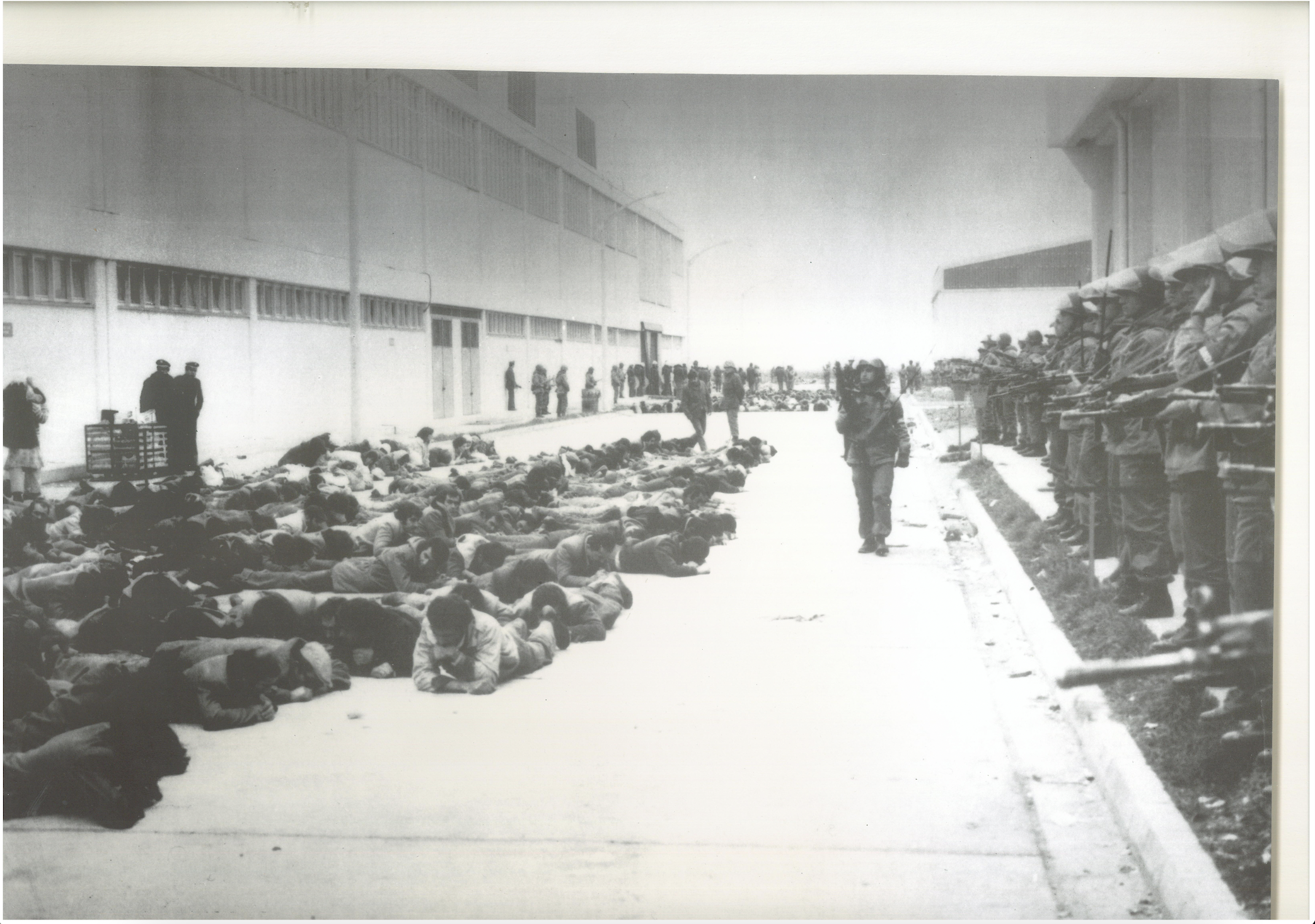

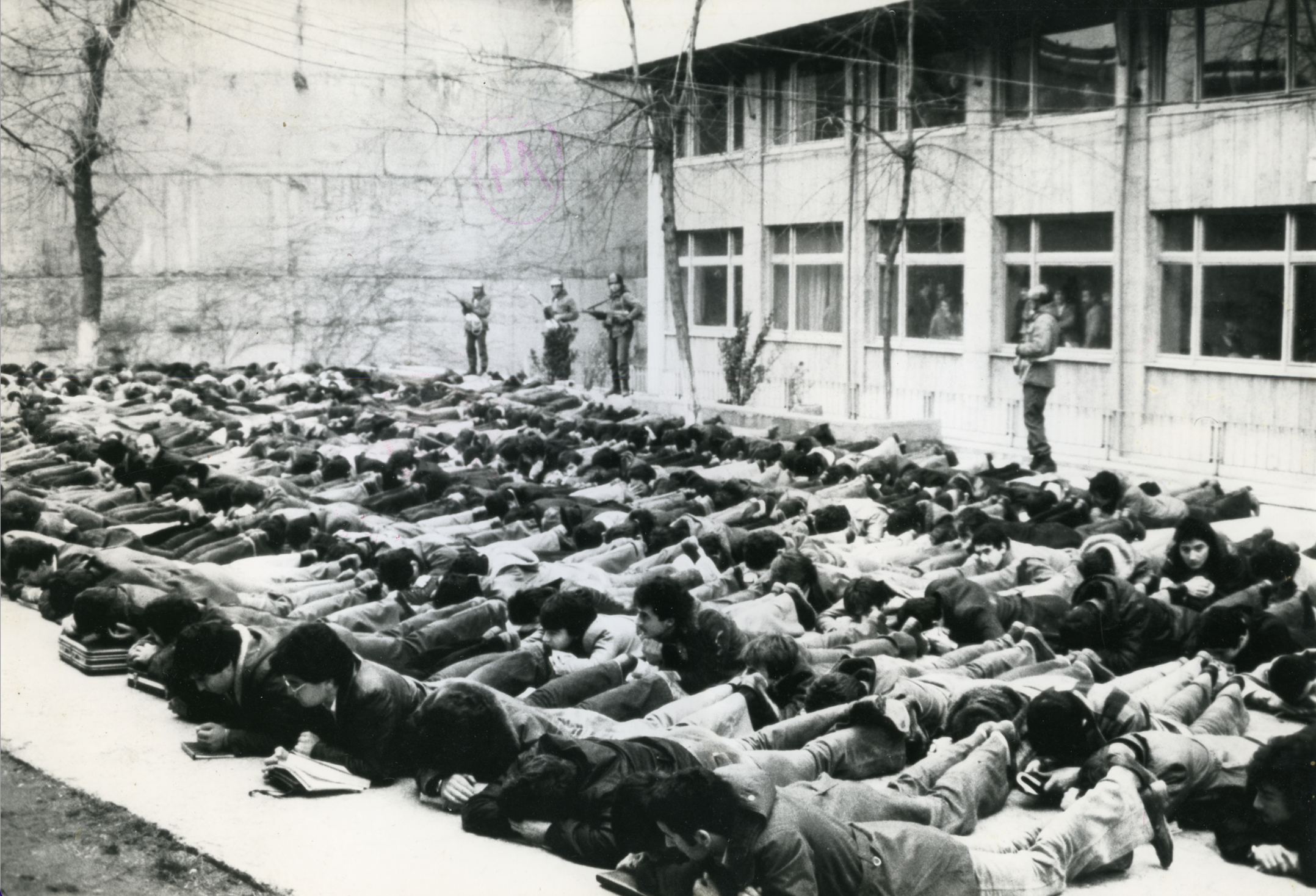

The earliest and most notable act of this process was to break the effect of socialist left on the general public opposition and to end its ability to set the social agenda. Immediately after the Coup, thousands of people were abruptly taken into custody from their homes and brought to police stations, police departments, public buildings, private estates and facilities that would from then on be used as places of torture. In these buildings, in addition to the military staff, the members of the police department and MİT (National Intelligence Organization) carried out tortures that would continue in an intensified manner during the next decade.

Torture was carried out by the military regime in a systematic and widespread manner on thousands of people, and consequently, practices that are considered as crimes in international law, including killings through torture, took place.

Even though the Military Coup particularly targeted the socialist left, some persons and institutions who were engaged with the nationalist/conservative politics were also subjects of crimes against humanity.

Ordinary daily life was ongoing despite the continuous torture, inhumane treatments and executions throughout the country. The sounds of the city blended into the cries of people under torture in prisons and police department buildings. While oppressive practices were covered up, the rebuilding of social and political life continued at full speed.

Unlawful trials in the martial law courts continued for many years. Surely the strongest pillar of such practices was the National Security Council which, in a chain of command, held the whole power of legislation, execution and jurisdiction in its hands.

The earliest and most notable act of this process was to break the effect of socialist left on the general public opposition and to end its ability to set the social agenda. Immediately after the Coup, thousands of people were abruptly taken into custody from their homes and brought to police stations, police departments, public buildings, private estates and facilities that would from then on be used as places of torture. In these buildings, in addition to the military staff, the members of the police department and MİT (National Intelligence Organization) carried out tortures that would continue in an intensified manner during the next decade.

Torture was carried out by the military regime in a systematic and widespread manner on thousands of people, and consequently, practices that are considered as crimes in international law, including killings through torture, took place.

Even though the Military Coup particularly targeted the socialist left, some persons and institutions who were engaged with the nationalist/conservative politics were also subjects of crimes against humanity.

Ordinary daily life was ongoing despite the continuous torture, inhumane treatments and executions throughout the country. The sounds of the city blended into the cries of people under torture in prisons and police department buildings. While oppressive practices were covered up, the rebuilding of social and political life continued at full speed.

Unlawful trials in the martial law courts continued for many years. Surely the strongest pillar of such practices was the National Security Council which, in a chain of command, held the whole power of legislation, execution and jurisdiction in its hands.

Identical to those in Argentina, Chile, Brazil and El Salvador, the military regime built with the 1980 Coup d’État completely reshaped the social, economic and political life in Turkey. The coup was unquestionably staged against the people and the Turkish Armed Forces had committed a crime according to the Article 146 of the Turkish Penal Code at the time.

Identical to those in Argentina, Chile, Brazil and El Salvador, the military regime built with the 1980 Coup d’État completely reshaped the social, economic and political life in Turkey. The coup was unquestionably staged against the people and the Turkish Armed Forces had committed a crime according to the Article 146 of the Turkish Penal Code at the time.

The perpetrators and supporters of the Coup, Kenan Evren being the foremost, based the Coup on the main reason that ‘the peace and security environment has ceased to exist because of anarchy’ in the country. To promote the military regime that the coup had built through prohibitions disguised as ‘building the democracy’, Evren visited all the provinces and many districts of Turkey and delivered speeches for acceptance of this new regime.

The perpetrators and supporters of the Coup, Kenan Evren being the foremost, based the Coup on the main reason that ‘the peace and security environment has ceased to exist because of anarchy’ in the country. To promote the military regime that the coup had built through prohibitions disguised as ‘building the democracy’, Evren visited all the provinces and many districts of Turkey and delivered speeches for acceptance of this new regime.

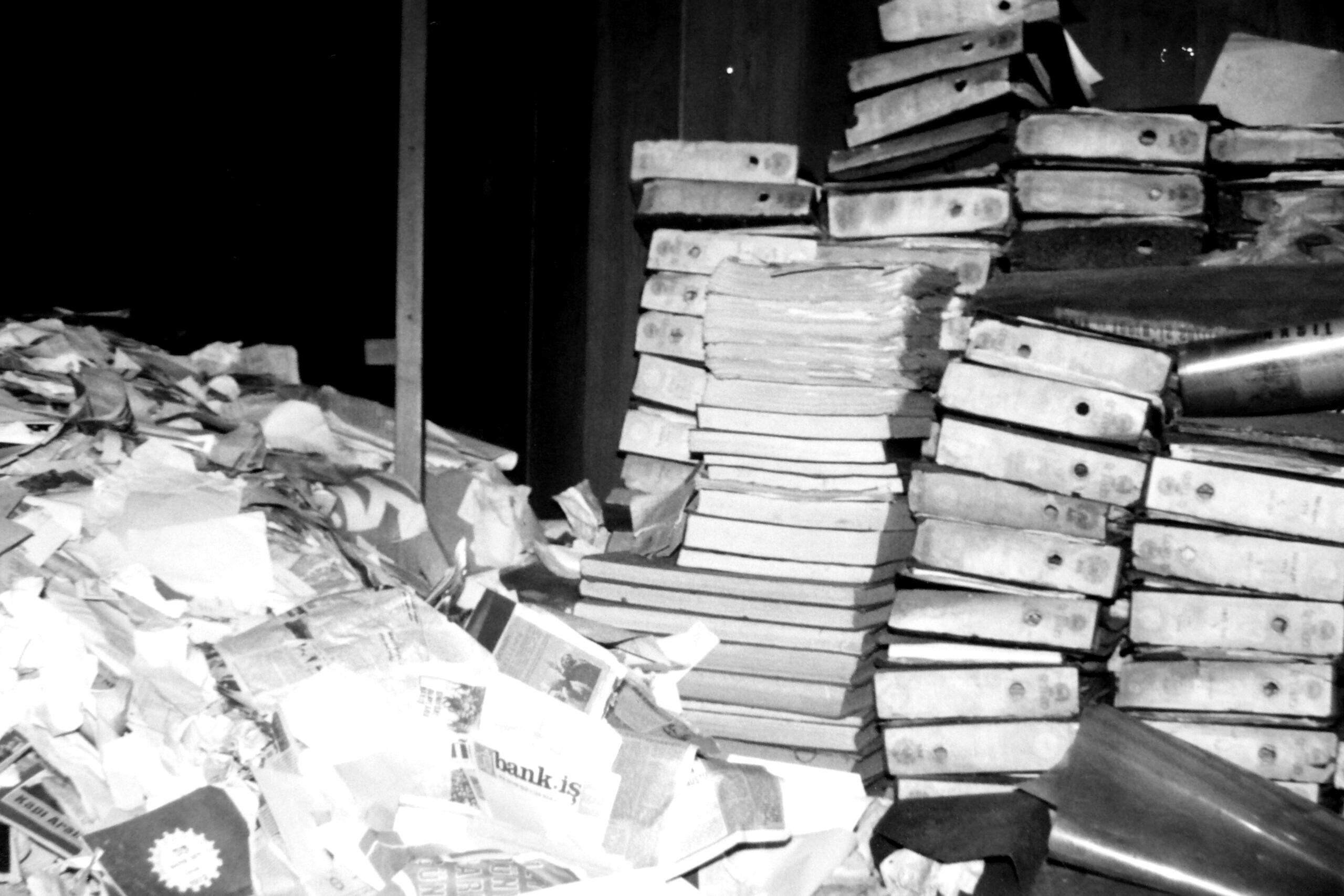

The Military Regime started banning everything that they equated to anarchy and terror. It abolished the political parties and abolished the right of organization, which is a democratic right, for all but the bourgeoisie. It banned the unions, occupational organizations, associations, and cooperatives. It ended the publication of many newspapers, banned thousands of publications. With new laws and practices that would ruin the autonomy of the universities and academic freedom, the military regime channeled the academic life and higher education to an irreparable route, the outcomes of which we are experiencing today.

The Military Regime started banning everything that they equated to anarchy and terror. It abolished the political parties and abolished the right of organization, which is a democratic right, for all but the bourgeoisie. It banned the unions, occupational organizations, associations, and cooperatives. It ended the publication of many newspapers, banned thousands of publications. With new laws and practices that would ruin the autonomy of the universities and academic freedom, the military regime channeled the academic life and higher education to an irreparable route, the outcomes of which we are experiencing today.

One of the main aims of the Military Regime was to institutionalize a new form of state and political regime and make it permanent. The prevailing Constitution of 1961 was an obstacle before this goal. Thus, a Commission of Constitution was formed within the Advisory Council, and this Commission, chaired by Prof. Dr. Orhan Aldıkaçtı, prepared the 1982 Constitution that was finally edited by the NSC. The Constitution of 1982 consecrated the State and provided it with an absolute precedence over the society and the individual. All the fundamental political and union rights and freedoms were unprecedentedly limited upon pretexts such as ‘the continuity of the state’, ‘national security’, ‘public order’ or ‘public morality’, that are open to discretionary interpretations. In the name of creating a strong state and a strong executive ability, the executive branch was empowered over legislation and jurisdiction. The decision-making mechanisms were more centralized via being collected under the auspices of the Prime Minister himself and the institutions that are directly attached to his office, or the Presidency and the National Security Council with their ever-increasing authorities. To strengthen the government against legislation, the Military Regime started a governance based on statutory decrees instead of laws.

One of the main aims of the Military Regime was to institutionalize a new form of state and political regime and make it permanent. The prevailing Constitution of 1961 was an obstacle before this goal. Thus, a Commission of Constitution was formed within the Advisory Council, and this Commission, chaired by Prof. Dr. Orhan Aldıkaçtı, prepared the 1982 Constitution that was finally edited by the NSC. The Constitution of 1982 consecrated the State and provided it with an absolute precedence over the society and the individual. All the fundamental political and union rights and freedoms were unprecedentedly limited upon pretexts such as ‘the continuity of the state’, ‘national security’, ‘public order’ or ‘public morality’, that are open to discretionary interpretations. In the name of creating a strong state and a strong executive ability, the executive branch was empowered over legislation and jurisdiction. The decision-making mechanisms were more centralized via being collected under the auspices of the Prime Minister himself and the institutions that are directly attached to his office, or the Presidency and the National Security Council with their ever-increasing authorities. To strengthen the government against legislation, the Military Regime started a governance based on statutory decrees instead of laws.

Judicial independence was impaired and judicial control was disabled. Through the pertaining provisions, the political parties were prevented from their bases in the society. Being subordinated to state control, political parties were limited in their activities and could now be barred easier. The new Electoral Law that prescribed a 10 % national election vote threshold sacrificed the principle of just representation for the sake of the executional stability.

Autonomy of universities was relinquished, universities were conjugated to the strict control of the Council of Higher Education (YÖK) and converted into state organs. The Army was at the center of the authoritarian state built by the 1980 Military Regime. The military bureaucracy was described as the third head of the executive power, in addition to the government and the president. The NSC was empowered and became more influential in every sense, as the soldiers predominated the seats.

Judicial independence was impaired and judicial control was disabled. Through the pertaining provisions, the political parties were prevented from their bases in the society. Being subordinated to state control, political parties were limited in their activities and could now be barred easier. The new Electoral Law that prescribed a 10 % national election vote threshold sacrificed the principle of just representation for the sake of the executional stability.

Autonomy of universities was relinquished, universities were conjugated to the strict control of the Council of Higher Education (YÖK) and converted into state organs. The Army was at the center of the authoritarian state built by the 1980 Military Regime. The military bureaucracy was described as the third head of the executive power, in addition to the government and the president. The NSC was empowered and became more influential in every sense, as the soldiers predominated the seats.

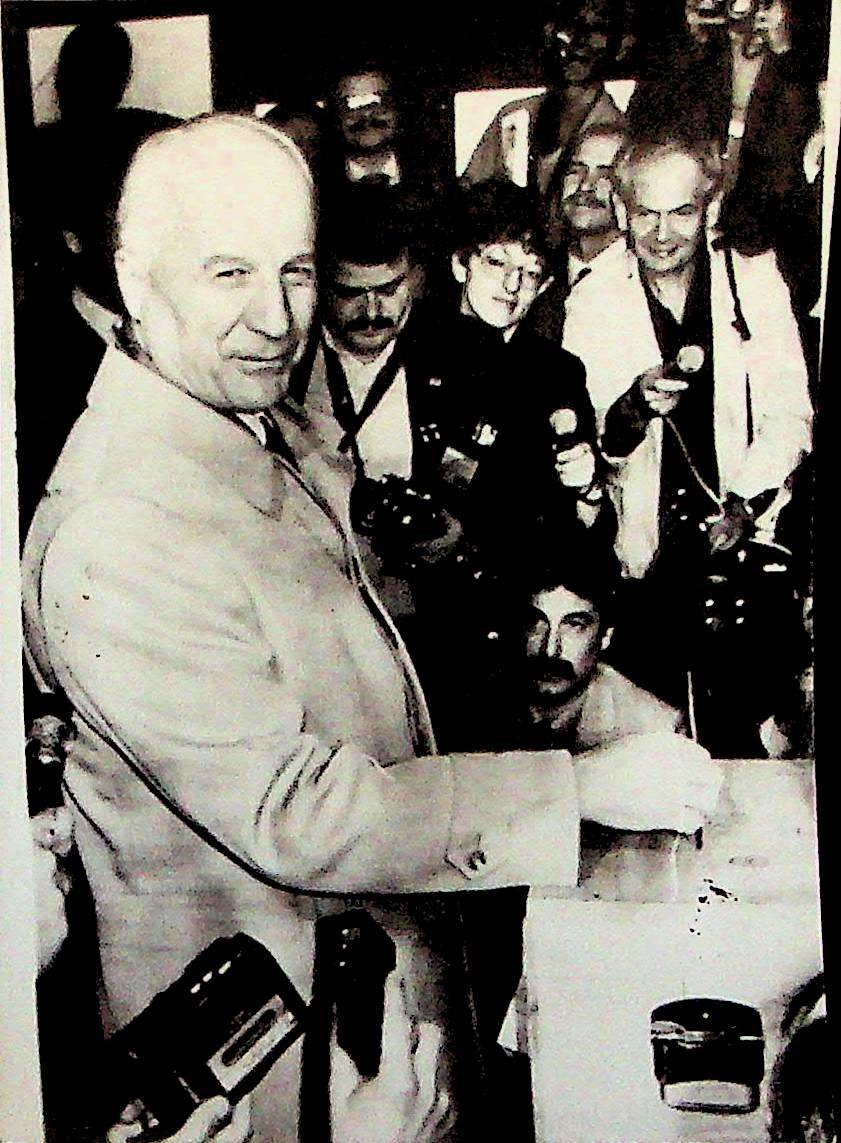

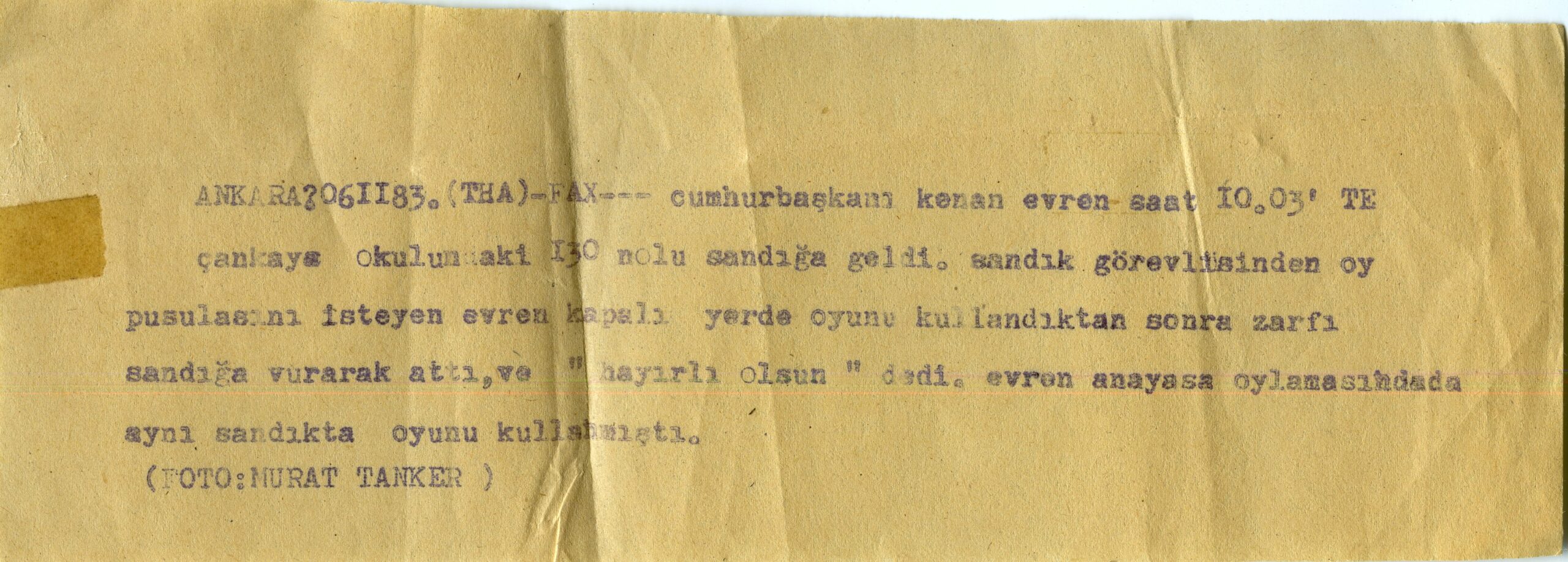

At the constitutional referendum held on November 7, 1982, the Constitution of 1982 was accepted with 91,37 % of the votes. This Constitution has since been repeatedly debated because of its antidemocratic structure. Kenan Evren said that in case the Constitution would be accepted in the referendum, this would mean that the public was ‘content with them’. As a result of the referendum, Kenan Evren became the President of Turkey and stayed in office until 1989. The Constitution of 1982, although undergone various referenda and changes, is still the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey.

At the constitutional referendum held on November 7, 1982, the Constitution of 1982 was accepted with 91,37 % of the votes. This Constitution has since been repeatedly debated because of its antidemocratic structure. Kenan Evren said that in case the Constitution would be accepted in the referendum, this would mean that the public was ‘content with them’. As a result of the referendum, Kenan Evren became the President of Turkey and stayed in office until 1989. The Constitution of 1982, although undergone various referenda and changes, is still the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey.

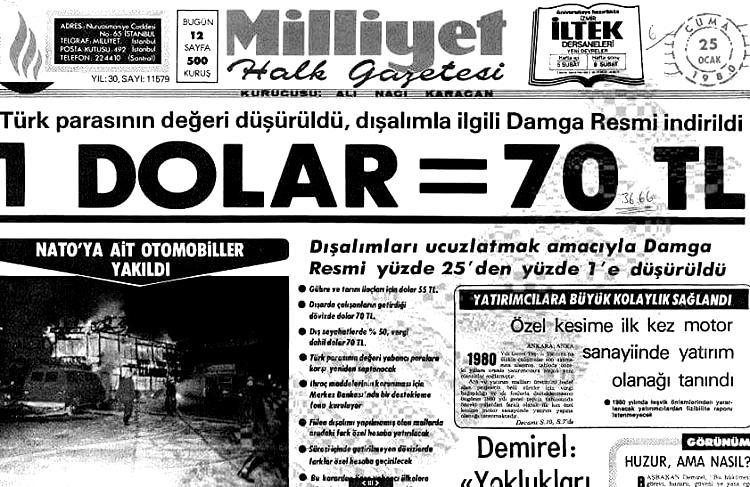

One of the biggest actions of the Military Coup and Regime of 1980 was to carry out the transition to a new regime of capital accumulation based on neoliberal policies. The financial decisions declared on January 24, 1980 aimed to establish a neoliberal economy. However, the strong working class opposition of the time and that the government was weak prevented those decisions to manifest as desired. With the Coup, the Military Regime brought Turgut Özal, who was the mastermind of the January 24 financial decisions, to lead the economy in Turkey, and put those policies into practice. Destroying the organized force of the working class, with the unions in the first place, was a prerequisite of this move. From this perspective, the class perspective of the 1980 Military Regime was obvious. All the capitalist organizations and financiers of the time, including TİSK (Turkish Confederation of Employer Associations), TÜSİAD (Turkish Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association), and TOBB (Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey) openly supported the Coup and the Military Regime.

One of the biggest actions of the Military Coup and Regime of 1980 was to carry out the transition to a new regime of capital accumulation based on neoliberal policies. The financial decisions declared on January 24, 1980 aimed to establish a neoliberal economy. However, the strong working class opposition of the time and that the government was weak prevented those decisions to manifest as desired. With the Coup, the Military Regime brought Turgut Özal, who was the mastermind of the January 24 financial decisions, to lead the economy in Turkey, and put those policies into practice. Destroying the organized force of the working class, with the unions in the first place, was a prerequisite of this move. From this perspective, the class perspective of the 1980 Military Regime was obvious. All the capitalist organizations and financiers of the time, including TİSK (Turkish Confederation of Employer Associations), TÜSİAD (Turkish Industrialists’ and Businessmen’s Association), and TOBB (Union of Chambers and Commodity Exchanges of Turkey) openly supported the Coup and the Military Regime.

The Military Regime halted the activities of DİSK and MİSK (Confederation of Nationalist Trade Unions of Turkey) and the unions that constitute them. The bank accounts of DİSK, MİSK and HAK-İŞ and associated unions were frozen. The directors of HAK-İŞ supported the Coup, declared that they do not engage in anarchist activities, and after a short while, in February 1981, their financial assets were reinstated, as they continued their activities. No action was taken against MİSK, whose activities were halted on September 12, 1980. The activities of Türk-İş (Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions), on the other hand, were not suspended after the September 12, 1980 Coup. Moreover, the directors of Türk-İş provided overt support to the Coup. Türk-İş Secretary General, Sadık Şide, served as the Minister of Social Security in the coup cabinet. Thus, it was the labor organizations that had an independent policy of class, and especially DİSK, which were targeted by the Military Coup. The directors and representatives of DİSK were taken into custody and tortured, and many of them were imprisoned for many years. There was a revocation case against DİSK, with the prosecution requesting death sentences for 52 of its directors. DİSK could only return to its union activities eleven years later, in 1991, when the case resulted in the acquittal of the accused.

In addition to the oppression against labor organizations, the Military Coup and Regime followed policies against left-wing political organizations, democratic mass organizations, universities and university students, Kurds, and Alevis.

In the social section that supported the Military Regime of 1980, all the fractions of bourgeoisie were present, in addition to the nationalist-conservative intelligentsia organized in Aydınlar Ocağı (‘the House of Lettered’), the political elite with similar views, most of the mainstream media, and broad social strata tired of the instability and crises in the country.

Following the 1980 Coup d’État, grave violations of human rights were carried out in a widespread and systematic manner in Turkey, ‘crimes against humanity’, especially with the tortures, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial/arbitrary executions, sexual violence and death sentences that became the practices of the period were committed.

The Military Regime halted the activities of DİSK and MİSK (Confederation of Nationalist Trade Unions of Turkey) and the unions that constitute them. The bank accounts of DİSK, MİSK and HAK-İŞ and associated unions were frozen. The directors of HAK-İŞ supported the Coup, declared that they do not engage in anarchist activities, and after a short while, in February 1981, their financial assets were reinstated, as they continued their activities. No action was taken against MİSK, whose activities were halted on September 12, 1980. The activities of Türk-İş (Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions), on the other hand, were not suspended after the September 12, 1980 Coup. Moreover, the directors of Türk-İş provided overt support to the Coup. Türk-İş Secretary General, Sadık Şide, served as the Minister of Social Security in the coup cabinet. Thus, it was the labor organizations that had an independent policy of class, and especially DİSK, which were targeted by the Military Coup. The directors and representatives of DİSK were taken into custody and tortured, and many of them were imprisoned for many years. There was a revocation case against DİSK, with the prosecution requesting death sentences for 52 of its directors. DİSK could only return to its union activities eleven years later, in 1991, when the case resulted in the acquittal of the accused.

In addition to the oppression against labor organizations, the Military Coup and Regime followed policies against left-wing political organizations, democratic mass organizations, universities and university students, Kurds, and Alevis.

In the social section that supported the Military Regime of 1980, all the fractions of bourgeoisie were present, in addition to the nationalist-conservative intelligentsia organized in Aydınlar Ocağı (‘the House of Lettered’), the political elite with similar views, most of the mainstream media, and broad social strata tired of the instability and crises in the country.

Following the 1980 Coup d’État, grave violations of human rights were carried out in a widespread and systematic manner in Turkey, ‘crimes against humanity’, especially with the tortures, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial/arbitrary executions, sexual violence and death sentences that became the practices of the period were committed.

Following the 1980 Coup d’État, grave violations of human rights were carried out in a widespread and systematic manner in Turkey, ‘crimes against humanity’, especially with the tortures, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial/arbitrary executions, sexual violence and death sentences that became the practices of the period were committed.

Those accountable for the Military Coup:

The superior command echelon of the Army who decided to carry out the 1980 Coup d’État, who governed the Coup, who created the legal and practical basis of the crimes against humanity committed during the period, and who took/carried out the decisions that enabled these crimes to be committed within the chain of command, are placed in the list of accountable military staff, for reasons explained in detail at the Museum.

The government of Prime Minister Bülend Ulusu, with all members of the Cabinet who accepted to carry out the tasks delegated to them by those who had staged the Military Coup, who thus participated in the crimes of coup, and did not interfere against committing the crimes against humanity, the members of the Advisory Council in the September 12, 1980 Period, and the Regional Governors of the State of Emergency are placed in the list of accountable political actors, for reasons explained in detail at the Museum.

Police Department and National Intelligence Organization Officials

The officials of the Police Department and MİT (National Intelligence Organization), who virtually committed the crimes against humanity –especially torture, enforced disappearance and extrajudicial/arbitrary executions-, who took part in and/or overlooked the torturing, who protected the offenders and prevented them to be tried, are placed in the list for reasons explained in detail at the Museum.

Civil Accomplices

This group includes individuals from all social and occupational groups who were not among the directors or the cadres of the Coup, but contributed to committing the crimes against human rights, cover-up of such crimes and the continuation of the ideology of the Military Regime as well as those who actively supported these acts. Doctors who did not report the findings of torture, teachers who blacklisted their students or informed on them, persons who denounced their neighbors and the silent witnesses also take part in this group.

Impunity is the legal or actual impossibility for the offenders of severe violations of human rights to be accused, apprehended, tried, or adequately sentenced when found guilty; or for the victims’ damages to be compensated. The offenders of the crimes against humanity that were committed during the period of the Military Coup of September 12, 1980 were protected through statute of limitations or shielded with excuses such as ‘state secrets’. The investigation and trials of offenders have been prevented for the last 42 years.

The Memory Museum for Historical Justice is designed as an active constituent of Turkey’s struggle for democracy and human rights. The Museum unites the fragmented stories of the 1980 Coup d’État around the struggle for historical justice, in order to crystalize the truth itself. We expect this more complete picture not only to hold those criminally responsible individuals guarded by impunity accountable, but also to strengthen intergenerational memory activism. We believe that it is futile to try establishing justice through reconciliation practices carried out solely by the government; but that this will only be possible through a dynamic process created with narrating the history bottom up, with open and accessible archives, and with the active participation of those targeted by the 1980 Coup d’État.

Impunity is the legal or actual impossibility for the offenders of severe violations of human rights to be accused, apprehended, tried, or adequately sentenced when found guilty; or for the victims’ damages to be compensated. The offenders of the crimes against humanity that were committed during the period of the Military Coup of September 12, 1980 were protected through statute of limitations or shielded with excuses such as ‘state secrets’. The investigation and trials of offenders have been prevented for the last 42 years.

The Memory Museum for Historical Justice is designed as an active constituent of Turkey’s struggle for democracy and human rights. The Museum unites the fragmented stories of the 1980 Coup d’État around the struggle for historical justice, in order to crystalize the truth itself. We expect this more complete picture not only to hold those criminally responsible individuals guarded by impunity accountable, but also to strengthen intergenerational memory activism. We believe that it is futile to try establishing justice through reconciliation practices carried out solely by the government; but that this will only be possible through a dynamic process created with narrating the history bottom up, with open and accessible archives, and with the active participation of those targeted by the 1980 Coup d’État.